On a lava plain in Iceland, eight shipping-container-size boxes on concrete risers suck in air with batteries of fans set in their sides.

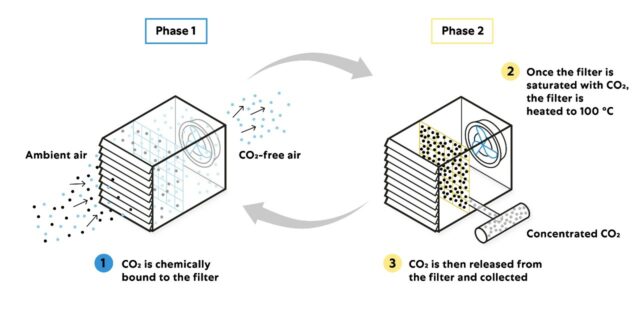

Filters inside the machines collect carbon dioxide until they’re full, at which point, the fans shut down. The interiors of the machines then heat up, releasing the CO2. The gas gets mixed with water and pumped deep underground, where it reacts with volcanic rock to form a stable mineral to remain forever.

This system, dubbed Orca by its builder, Climeworks, is the largest of its kind in existence. Even so, at 4,000 tons of carbon removed per year, it can’t make more than a tiny dent in the at least five gigatons scientists agree is needed.

However, Climeworks is far from the only organization pursuing what global experts now say is a crucial step in combating climate change: direct air capture (DAC). And, thanks to the U.S. government’s recent allocation of $3.5 billion for DAC, the field is about to get a lot more active.

The need for direct air capture

DAC is distinct from conventional carbon capture’s focus on point-source capture, which collects carbon dioxide at the point of emission, as in, for example, a power plant smokestack. Point-source capture seeks to mitigate ongoing emissions, whereas DAC aims to put the carbon genie back in the bottle by reducing carbon already in the air. Either way, captured carbon can be used in other processes like soft drink carbonation, or it can be pumped underground or otherwise removed from the environment.

“Carbon removal is the only way to address [the] harm that’s already happened from legacy emissions,” said Anu Khan, deputy director of science and innovation at Carbon180, during a webinar on carbon removal hosted by American University’s Institute for Carbon Removal Law & Policy.

Carbon removal is the only way to address [the] harm that’s already happened from legacy emissions.

—Anu Khan, deputy director of science and innovation, Carbon180

In other words, society has to stop emitting and draw down what’s already there to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius and avoid catastrophe. That’s the verdict of the Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change report released by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in April. “It’s a marginal community arguing that we can get to 1.5 degrees without CDR [carbon dioxide removal],” clarified one of the report’s lead authors, Greg Nemet. He spoke on the webinar with Khan.

Five to 10 gigatons of CO2 will have to be removed per year by 2050, Nemet said in the webinar. That’s in addition to reaching zero net emissions. It’s a tough challenge, both from a technical and a financial perspective.

Technical hurdles

Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased from 280 parts per million (ppm) before the Industrial Revolution to more than 412 ppm in 2020. That’s a big jump, and it’s already causing havoc with weather systems and more. But it still represents a small percentage of atmospheric gases.

That means, to remove just one ton of carbon dioxide from the air, any DAC device has to move more than 3,000 tons of air, according to Shantanu Agarwal, CEO of DAC startup Sustaera. “So it’s a massive amount of air you have to process to get one ton of CO2 out,” he said.

Moving all that air takes also takes a lot of energy, a problem Climeworks solved in Iceland by colocating with a geothermal plant. Green energy will have to power any DAC plant since using fossil fuels would simply put carbon back into the atmosphere at one end of the system even as it withdraws it at the other.

Simply planting more trees and turning to agricultural solutions won’t cut it, Agarwal and Nemet agree. “Fires, change in political parties, or change in human population or use conditions might take away that forest you planted 20 years ago,” Agarwal says. Nemet cites pressures on global food supplies as barriers to turning over large amounts of land to carbon sequestration.

So, technological solutions will have to play a critical role in drawing down carbon. However, paying for them presents its own challenges.

Financial challenges

Until recently, DAC developers have been hampered by a scarcity of funding for their efforts. After all, it results in a product—captured carbon dioxide—that needs to stay out of circulation to do the most good. Nevertheless, to keep going, DAC startups have turned to selling CO2 as a commodity even when doing so runs counter to their goal of reducing atmospheric carbon.

For example, Climeworks rival Carbon Engineering in British Columbia has partnered with oil company Occidental to complete a one-million-ton DAC plant in the southwestern U.S. in 2024. Occidental will pump the captured carbon dioxide underground to help push oil to the surface. Of course, burning the oil will release carbon back into the atmosphere.

Carbon Engineering says it wouldn’t have the money to build that first, large-scale plant without Occidental as a customer and that going forward, it won’t have to rely on oil revenue.

Climeworks has also had to sell CO2 to fund its broader aim to reduce atmospheric carbon, including to soft drink bottlers and for use in greenhouses, although it says it won’t partner with oil companies. In April, it raised $650 million to build a plant capable of capturing 40,000 tons of carbon—the largest amount raised by a DAC company so far.

Corporations have also begun stepping up by investing in carbon removal projects. For example, Stripe’s Frontier Fund has taken in $925 million from companies, including Alphabet and Shopify, to invest in carbon removal. It’s the start of a market for captured carbon that stays put for the greater good.

But DAC could really take off with the help of the U.S. government’s multi-billion-dollar investment.

A $3.5-billion boost

In November, the U.S. government gave DAC a major boost in the form of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The new law allocates $3.5 billion for four DAC hubs, each to remove 1 million tons of CO2 per year.

The details still need to be worked out, including locations for the hubs, but the IIJA money represents the biggest outlay yet for DAC. It’s roughly equal to the annual budget of DARPA, the government agency that launched the internet and many other breakthroughs, and it could change the game for DAC.

“This significant amount of capital, if deployed in a careful, thoughtful manner, can do a significant amount of good,” Agarwal says. “Because the technologies we’re talking about are hardware technologies, they take a lot of capital, a lot of time to commercialize.”

This significant amount of capital, if deployed in a careful, thoughtful manner, can do a significant amount of good.

—Shantanu Agarwal, CEO, Sustaera

It’s in cases like that where government funding can get projects off the ground before commercial incentives fully develop. It’s how the U.S. got to the moon and launched the internet—projects that returned a lot of value without initially turning a profit.

Agarwal expects the U.S. Department of Energy to invest some of the $3.5 billion in small-scale DAC projects to see what technologies work best. “We don’t have a lot of time, so we need to be able to take significant risks on these technologies,” he says.

Agarwal, for one, is counting on what he says is his company’s unique sorbent technology to capture carbon from the air more efficiently than his competitors. The trick, he says, is to use activated alkali metal compounds in the sorbents rather than the amine technology used by Climeworks and others. “Amines are the most established carbon capture technology. However there are some challenges with amines, which people are working to solve.” He says his company has sidestepped the issue with its technology. Among the advantages Agarwal cites: lower cost and greater durability.

“There is an enormous amount of work to do,” Kahn said in the recent webinar. “We need removal to bring temperatures back down.” Nevertheless, she remains optimistic about the future of carbon capture tech. “We’re in an inspiring spot.”

Lead photo courtesy of Climeworks