By Kelly Kearsley | Photography by Samara Souza

Growing up in the Amazon rainforest, Luziete Mar Hipy quickly learned that education wasn’t a given. There was no school in her town, one of 12 tiny communities built along the 834-square-mile Rio Amapá Sustainable Development Reserve (SDR) in northern Brazil. She started kindergarten in a neighboring community, but the long commute proved challenging.

“I ended up giving up on my studies,” Hipy, 24, recalls. She eventually resumed school a few years later when one opened closer to her home. She attended high school in a larger town in the SDR. Hipy’s childhood story highlights the struggles that rural communities in the Amazon face in accessing modern services, including schooling, healthcare and job training. Community members are forced to make tough decisions to either travel far distances to get modern services or forgo their studies as Hipy did. These challenges indirectly contribute to deforestation as illegal logging and mining jobs prove easier to come by and more lucrative.

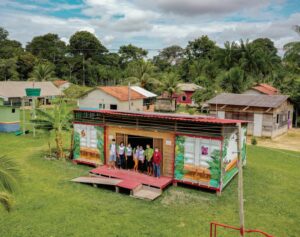

However, the story in the Amazon is changing, thanks to innovative technology and a lot of perseverance from Hipy and others who are dedicated to improving the lives of the people in their community. Hipy is now the director of the Boa Esperança Solar Community Hub (SCH), an internet center deployed in July 2021 that’s delivering digital education to the Amazon.

“The project is benefiting many young people with the opportunity to participate in higher education and vocational courses and preparing them for the job market,” she says. “In addition, it has been helping many community members, mainly in the educational and employability areas.”

The Amazon—and its communities—at risk

The people who call the Amazon home have long relied on the rainforest to sustain them, harvesting trees, nuts and oils and mining the earth for gold, copper, tin, nickel and other metals. But deforestation and extraction are taking a toll. According to Brazil’s space research agency, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, deforestation recently hit a 15-year high. The study found that 5,110 square miles of rainforest disappeared during 2020–21—the most since 2006.

Marilson Silva, an environmental monitoring coordinator for the Foundation for Amazon Sustainability (FAS), says that education and employment challenges in the region can make illegal mining and deforestation activities more attractive. “It’s an easy-to-earn alternative for young people,” he says. The lack of distance learning opportunities, advancement courses and training for new jobs leaves few options for the indigenous communities. There’s also limited environmental monitoring and little information about the importance of conservation and sustainable resources.

The FAS is focused on education to improve sustainability. This is where the SCH in Boa Esperança—a central location that serves a dozen outlying communities—has made a big difference. In partnership with Dell, Computer Aid, Intel and Microsoft, the SCH was deployed.

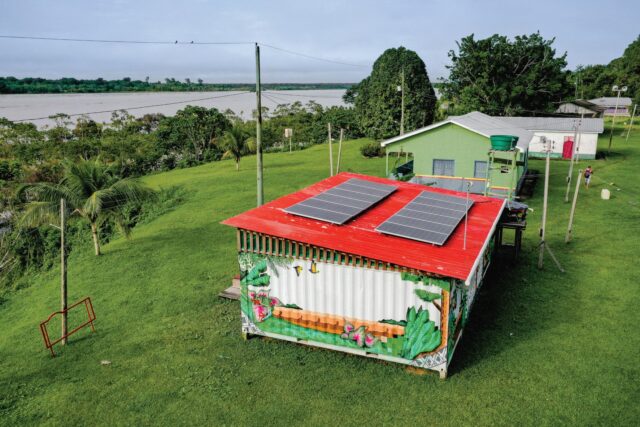

SCHs are built in-country, supporting a circular economy by using refurbished shipping containers that would otherwise be scrapped. These structures use low consumption energy technology and solar panels as a source of energy. Once installed, the SCHs run on renewable energy. In the case of the Amazon location, sustainably sourced wood and furniture are also being used.

Access to computing power has opened up a world of opportunities for the region’s residents. Silva notes that the SCHs enable education through computer classes and access to online courses, as well as training for young people eager for new economic opportunities. They also provide telemedicine and health services to members of the community, in addition to offerings that meet site-specific community needs. And, as part of the FAS initiatives, they facilitate environmental training and monitoring, which encourages local community members to record and communicate information about forest use in the area.

The tech behind the tech

The SCH in Boa Esperança is one of 25 such facilities that Dell has helped create worldwide. There are locations in Nigeria, South Africa, Mexico, Morocco, Colombia, Kenya and Brazil. The project began in 2013 to bring skill development to underserved communities in remote areas.

Ruan Malherbe remembers working on the first solar project for a tiny village in South Africa. These initial locations began as Solar Learning Labs, which were essentially smaller versions of the hubs—though they still used the same solar concept to power computing—and were primarily focused on remote learning. “These places are just very rural—it may take six hours of driving on a dirt road to get there,” he says. The original concept entailed converting a single shipping container into a ready-made computing center that could be dropped into place. The solar panels ensure that the computers have power, even if the community is far from a traditional electrical grid.

Converting the shipping containers and adding solar was relatively simple, Malherbe, client solutions technologist at Dell Technologies, says. But figuring out how to get enough power for computers, operating systems and applications, along with reliable internet, was more challenging. That’s how Malherbe became involved. He has expertise in thin clients, which are computers and applications that run off a centralized server instead of a local hard drive.

“When we first started, the technology wasn’t as flexible and usable as it is today,” Malherbe says. The computers couldn’t handle any media-rich content because download speeds were so slow. Back then, the communities mostly used the labs to learn how to use computers and operate standard applications.

As the technology has evolved, so has the project. Dell and its partners have shifted their strategy from building labs to creating the larger SCHs, which are double the size. The sides and windows open to create an environment similar to an internet café, complete with accessible Wi-Fi. “So you can work in the hub or take a rugged netbook or mobile device and go sit under a nearby tree,” Malherbe says. Each SCH is equipped with Dell computers and networking gear designed to run on a thin-client network with minimal power needs. These products were selected for durability, long life and energy efficiency.

For Malherbe, witnessing the young kids’ excitement in these rural areas has made the work of configuring the SCHs more than worth it. The projects have reached more than 18,000 students and facilitated more than 10,000 hours of digital learning per location in eight years.

“Whenever we implement one, we have kids coming to us every 10 seconds wanting to look inside or ask questions,” Malherbe says. “It’s a nice feeling to see what we can achieve when we put the technology and people together.”

Each SCH is unique in the way it addresses community needs by providing services beyond education. Leveraging health services capabilities in Boa Esperança, for instance, is an example of such local specificity.

When digital means sustainable

In Boa Esperança, Rivelino Claro Carvalho found new work and new confidence at the SCH. He’s lived in the region for 35 years, and his family has always worked in the fields or mines. He started using the SCH to communicate with relatives and friends who live far away and to connect with healthcare providers.

His involvement led to a job with FAS, where he works as the head of telehealth, maintenance and operations for the SCH.

“The first conversation I had with FAS, I was scared, but I soon realized that I was capable of doing the job,” he says. “I had the support of FAS employees, and I repeated to myself, I am capable, and I will handle it.”

Carvalho, 42, notes that the benefits of the SCH have impacted the entire community. Residents now have access to the internet, which has “improved communication, the availability of potable water, medical care, vocational courses and income generation,” he says.

Hipy adds that the SCH is giving a new generation of Amazon residents access to digital tools and new paths for their future. “The educational support for young people has been fundamental and has had a great result,” she says. “Many of them are taking distance learning courses and do not need to travel from their communities and homes to the city for this.”

Notably, the Brazil project can only exist in the region if the residents agree to the terms of the Bolsa Floresta program, a government initiative that aims to decrease deforestation through community building.

“The families understand that the projects come to them because they comply with the rules, such as not carrying out deforestation,” Silva reports. The residents must also harvest other forest resources in a manner that doesn’t compromise the forest’s resilience.

The result is a full circle effect: The SCH helps improve the lives of the people living in the Amazon and, in doing so, the SCH helps cultivate a more sustainable relationship between the rainforest and its residents. Most impactfully, this unique center transforms lives and enables community members to live and work in the region for generations to come.

Want to read more stories like this? Check out Realize magazine.