Ryan Lewis will tell you: Decreasing one’s carbon footprint is a lot like playing the game of whack-a-mole.

Take a specific sector like food. Buy a product with low packaging, and you might have to worry about farming practices. Buying organic tomatoes is good, but what if they are from halfway across the world? For conscious consumers, even “carbon in and of itself is not the whole story,” says Lewis, the CEO of Earthhero.com, an online retailer of eco-friendly products. Fair labor practices, for example, come into play, as well.

Food’s distasteful footprint

Food is an especially attractive target to place under the microscope to meet carbon reduction goals, as it comprises 10% to 30% of a household’s carbon footprint. Consumption of goods and services, transportation and household energy make up the rest of the pie.

But the task is easier said than done. “One of the challenges with reporting the carbon footprint of grocery items is that the same food product grown in one region can have a completely different carbon footprint in another region,” says Kim Arrington Johnson, principal analyst at ABI Research.

“For example, tomatoes or lettuces grown in a warm, sunny Mediterranean country will have less of a carbon footprint than the same products grown in a heated greenhouse in northern Europe,” Johnson continues. The factors consumers have to make when purchasing a responsible product are not only dizzying in number, they are often based on inadequate information. As a result, they often don’t know where to look. “The average consumer is not going to do a spreadsheet analysis for each and every product and how they live their life,” Lewis says.

Lightening the load

To decrease the overwhelm, B2B companies and consumer-facing apps are promising to do the math. They crunch the carbon footprint of food products and deliver them in easy-to-understand language that might influence purchasing decisions at the grocery store.

The company GreenSwapp, for example, is a B2B carbon-tracking service for supermarkets, food brands and food apps that calculates product-wise climate impacts at scale and communicates them via “climate labels.” The labels are colored red for high carbon footprint, orange for medium and green for low. “The CO2 data allows [retailers] to detect high-impact products and ingredients and avoid selling them in the first place, thereby reducing impact at scale,” says Ajay Varadharajan, founder and CEO.

Consumer-facing mobile app Evocco enables users in the Republic of Ireland to take a picture of their receipt and delivers a net carbon footprint score. Evocco uses optical character recognition to read text and then identify products purchased. It then matches the product against the company’s database to give it a rating.

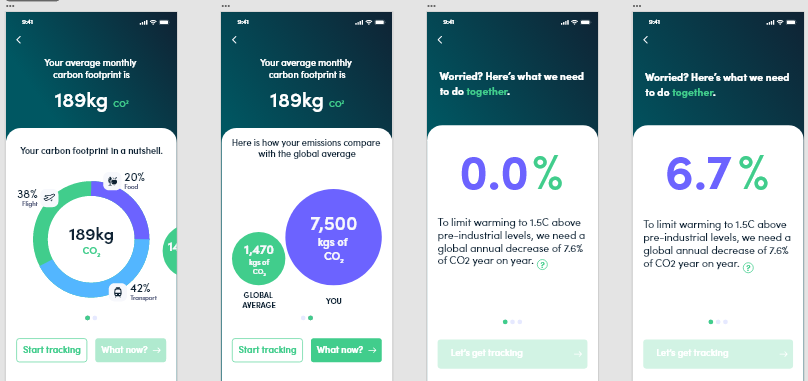

The app Capture uses information about the consumer’s mobility and food choices to deliver ongoing updated information about their carbon footprint.

While these companies are working hard to deliver accurate information about the carbon footprint of food, the calculations are not easy.

The complicated calculations for food carbon

“Outside of the largest food brands that can demand suppliers to record raw data in environmental management systems, a large portion of the world’s food supply chains don’t record any data today,” Varadharajan says. “Aggregating product attributes on each product’s supply chain is notoriously difficult. While there are several initiatives that do a good job investigating parts of the supply chains, overall product data are disparate, inaccessible, lacking standardization and incomplete.”

“Mandating this, just like how nutrition data was mandated decades ago, would be a good start to solving a lot of these issues,” he adds.

Fortunately, there are a few sources for accurate data. To deliver a green, orange or red carbon footprint rating, companies like GreenSwapp first need to calculate the carbon footprint of the foods at the stores. In many cases, this information is available publicly in peer-reviewed literature. GreenSwapp aggregates the information in the scientific research and standardizes them to accommodate for varying scopes of analyses. It assigns the median value of the data points gathered, to represent the product. Processed foods’ footprints are calculated by breaking them down into ingredients found in the databases.

The company also ensures all parameters like transportation and packaging are even, gathering supply chain information from public domain databases. They check that they’re comparing apples to apples. GreenSwapp’s processes comply with international standards like the ISO 14001 and GHG Protocol. The company does not take the carbon impact of cooking or disposal of food into account when calculating the carbon footprint of grocery items.

Given the complexities of tracking food footprint, apps like Capture simplify the process by zeroing in on the biggest offenders: meat, which contributes more than half of food’s carbon footprint, according to the Center for Sustainable Systems at the University of Michigan. When considering their food’s carbon footprint, consumers “tend to think that locality or miles traveled by food is the most important indicator of climate impact, which is understandable given that it’s a very visual indicator—further away means more transportation emissions,” Varadharajan says. But, he goes on to explain, transport accounts for very little of total emissions. (One report estimates it makes up only 5% of the average U.S. household’s food emissions.)

Shifting your diet

“Focusing on what you eat, especially increasing the consumption of plant-based foods, is the way that a person can substantially reduce their personal carbon footprint,” Johnson says. Indeed a 2021 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) advises lowered meat consumption as an important way to reduce the impact of global warming.

With that in mind, Capture’s CEO, Josie Stoker, says that “when it comes to emissions from food, we chose to focus just very specifically on the amount of meat in a diet. That amount has a massive impact on how sustainable your diet is.” Capture uses carbon footprint data from U.K. government sources such as the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). Capture’s team is keen on addressing more areas of a consumer’s footprint—from mobility to food and, in the future, home energy use.

Positivity and gamification will be key to consumers adopting the apps, Stoker says. Capture, which has been downloaded over 100,000 times since its launch in 2020, has studied the models developed by the health industry, which uses fitness goals as milestones to achieve. Similarly, Capture helps consumers understand their baseline emissions and subtracts 7.6% from them.

“That’s the amount we would need to decrease emissions year on year between 2020 and 2030 to meet warming targets,” Stoker points out. The app, which is also available to organizations for use as part of team exercises, shows you whether or not you’re on track to meet monthly targets. Users can check in to see goals and read articles about decreasing carbon footprint.

While companies and industrial activity are responsible for a significant chunk of the global carbon footprint, there is notable interest among individuals to decrease their own share. Johnson points to a 2021 Global Sustainability Study of more than 10,000 people in 17 countries, which indicated that 85% of respondents have shifted their purchasing behavior toward being more sustainable in the last five years.

Businesses like Capture are ready to help fuel this momentum. “We’re making sure that the [Capture] app is open and accessible to somebody that’s just starting out on that journey and looking for initial steps,” Stoker says.

Lead photo by Tara Clark/Unsplash