Recently, my colleague Prasad Thrikutam and I had the pleasure of hosting a technical session on the topic of the Cognitive Enterprise at the 2016 CIO 100 Symposium and Awards. Together, we took some of the most cutting-edge CIOs on a journey to what the requisite future state of enterprise cognition should look like.

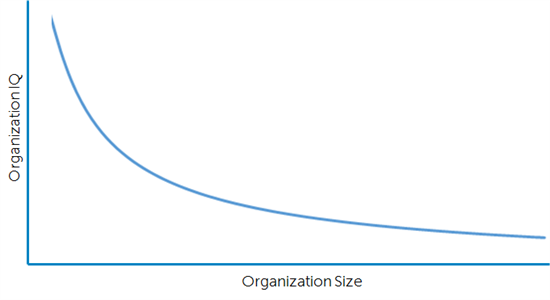

In case the term “cognitive enterprise” isn’t familiar to you, let’s start with one of the mysteries of organizational dynamics – the seemingly unbreakable inverse relationship between the size of an enterprise and its inability to act intelligently.

This has everything to do with size and nothing to do with the intelligence of the people who lead, manage, and staff the business.

It’s as if there’s an impenetrable barrier that prevents the considerable intelligence available in a business from influencing the behavior of that business.

Large organizations don’t, that is, act with a coherent purpose. Large enterprises operate according to an industrial model – a model sometimes described as “an organization designed by geniuses to be run by idiots.”

The driving philosophy of most business process design is “Simplify, simplify, simplify.” Depending on the process and its goals, this often is the best answer. In truly industrial situations — manufacturing and its analogs, where the goal is to create large numbers of identical work products — simplification and standardization make all kinds of sense.

It isn’t that simplification is a bad thing. When the subject is business infrastructure, the applications portfolio, or, as mentioned, industrial processes, simplification is an essential pre-requisite to enterprise cognition, just as inside your head the alternative to clarity is confusion.

But with few exceptions, business is first and foremost a game. It’s about winning and losing. In the short term, it’s pretty close to a zero-sum game, where one company selling more products to more customers means some other business will find itself selling fewer products to fewer customers.

There just aren’t that many games where success comes from streamlining, simplifying, and standardizing. In football, the winning teams aren’t the ones with the skinniest playbooks. In baseball, pitchers don’t throw every pitch exactly the same. If they did, they’d get shelled.

If you don’t like athletic metaphors, consider chess. Think a grandmaster is going to win by always playing the same opening?

A military strategist, Colonel John Boyd, figured out the key to beating competitors in a wide variety of contests. He called it the OODA loop, for Observe, Orient (another word is “interpret”), Decide, Act. It’s a loop because when you act you change your environment, so you have to observe the changes.

In time-bound competitions whoever has the faster OODA loops wins, because getting to action faster changes not only your own environment but your competitor’s situation as well. This makes your opponent’s observations, orientation, and decision-making obsolete – he, she, or it has to start over.

OODA is a pretty good model general-purpose model for thinking, too. When you solve a problem, you assemble the facts of the matter (observe), figure out what they mean (orient), choose a course of action (decide), and execute your decision (act).

We humans are pretty good at this. We each know how to act with purpose.

Large enterprises? Not so much. Few large enterprises act with purpose. Even when a CEO sets strategy, most organizations consist of rival siloes with high walls and independent purposes. Cooperation and collaboration isn’t in their nature – quite the opposite; the compensation system usually rewards executives for the success of their siloes, whether or not that success translates to success for the business as a whole.

This is why entrepreneurs are able to outcompete enterprise-scale competitors. They can smell an opportunity and chase it, and the whole company of maybe 50 people chase it right alongside.

They aren’t, that is, cognitive.