Walter Isaacson:

It’s midnight, August 16th, 1969 on a dairy farm in Bethel, New York, and the most transformative music festival of the 20th century is in full swing, Woodstock. Four hundred thousand people have gathered, braving the rain and mud to hear some of the decade’s most legendary artists, such as Jimi Hendrix, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Crosby, Stills and Nash. But the festival is in danger of coming to a crashing hall.

Walter Isaacson:

Joel Rosenman, one of Woodstock’s founders, has just been told that the evenings headliners, The Who and the Grateful Dead, won’t perform unless they’re paid up front, but Rosenman doesn’t have their money on hand.

Joel Rosenman:

And so I asked, “Well, what happens if we tell the crowd that The Who and Grateful Dead aren’t going to play?” And he said, “You don’t want to know that. It won’t be pleasant.”

Walter Isaacson:

That gives Rosenman about two hours to come up with the $30,000 he needs to pay his headliners and save Woodstock from potential disaster. So Rosenman calls Bethel’s local banker, Charlie Prince, and explains the situation. Prince says that he can’t access his vault. However, there’s a small chance that he might be able to find some cashiers checks at the bank, but there’s a more immediate problem that needs to be addressed first.

Joel Rosenman:

He said, “Yeah, I can get into the bank, but I can’t get to the bank. The two and a half miles between me and the bank are essentially a parking lot full of vehicles, and there’s no way I could get in my car and do that.” I said, “Don’t worry about that.”

Walter Isaacson:

Luckily, Rosenman has access to a helicopter that the festival’s using to transport performers. So he orders the chopper to Prince’s house, hops on his motorcycle, and zips off to meet the pilot in town. When Rosenman arrives, they jump in the helicopter, and a few minutes later, Prince unlocks the doors to the bank while Rosenman nervously paces outside.

Joel Rosenman:

And I could hear from somewhere in the bank, this whoop of surprise and delight. “I found them.” He said, “I found them.” About five minutes later, we were back to his place, and at that point I jumped on my motorbike.

Walter Isaacson:

With cashier’s checks in hand, Rosenman weaves his motorbike through the cars, desperately trying to get back to the festival in time for The Who and Grateful Dead to take the stage.

Joel Rosenman:

I remember coming over the hill, the top of the festival, and looking down at it. It was midnight, except the stage was ablaze with light, and most of it was on Janice Joplin wearing a sparkly kind of dress and looking bigger than life, in a sense, like a jewel. And I descended into the crowd on my bike and threaded my way through that crowd to the stage. I remember thinking, “These people look like a big family, but they can’t know each other, certainly not all of them.” I made my way to the stage, gave the cashier’s checks to the managers, and the Grateful Dead and The Who played.

Walter Isaacson:

Fifty-three years later, Woodstock is regarded as a pivotal moment in the history of pop music that helped establish the music festival as a major cultural event in North America. Even though Joel Rosenman experienced some big financial hurdles during Woodstock, the festival helped birth a new industry. In fact, in 2017, Coachella pulled in $114 million in profit as part of an industry that’s now worth over $31 billion worldwide. Today, hundreds of festivals are held around the world every year, and the people organizing these events are taking the festival beyond a massive multi-day musical event. They’re designing unique and immersive experiences that inspire whimsy and delight, but more than anything, these events and their organizers are helping to create community by building a meaningful, shared experience.

Walter Isaacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson, and this is Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Speaker 3:

This is found in the music and the dress and the clothing and the bizarre.

Speaker 4:

I would rather have you hear them in a concert type situation where they’re just playing like for an hour, an hour and a half.

Speaker 5:

It is a fusion of musical genius, technical virtuosity.

Speaker 6:

Achieving natural balance between all instruments.

Walter Isaacson:

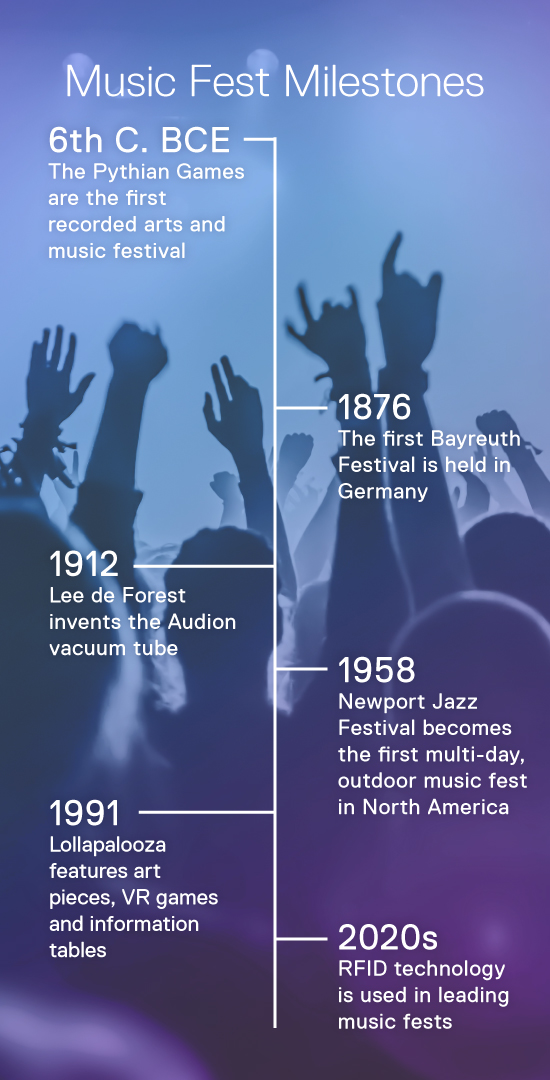

In the decades following Woodstock, the music festival has come to symbolize a human need for belonging and amusement, and while today’s festivals are firmly rooted in youth culture, ancient festivals were a devoted service to the gods. The first recorded arts and music festival was the Pythian Games, a precursor to the Olympics, which began in the sixth century BC, at the sanctuary of Apollo in ancient Greece.

Gina Arnold:

The Pythian Games were held every two years in Delphi in Greece.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Gina Arnold, author of Half a Million Strong: Crowds and Power from Woodstock to Coachella.

Gina Arnold:

They were in honor of Apollo, who was the God of many things, but the Pythian Games were meant to celebrate his victory over a python that was miles and miles long that he slew with arrows. There were races, there was athletic games, there were poetry recitations, all kinds of tributes, lots of animal slaughter.

Walter Isaacson:

And there was also music. These early Greek festivals were not only meant to appease the gods. They were also created to entertain them, but these festivals weren’t just for the gods. They were also joyful celebrations where common people could let loose, escape the difficulties of daily life, and be part of something bigger than themselves.

Gina Arnold:

I think that they probably felt very much like the festivals that we go to today. They probably spent the night and camped. The music would’ve sounded really different to our ears. They used a lot of different instruments that would’ve probably sounded like cacophony to us. This was what gave people something to look forward to, and the Greeks were big on public display and on the idea of people coming together. It’s a place where people gather to make their needs known and to celebrate. Music festivals are where people go to experience history emotionally. They want to be part of history.

Walter Isaacson:

In the Middle Ages, festivals were still closely tied to religion, but they started to move indoors as Christian worship began to replace existing pagan festivals. In fact, music became an important draw for new church goers unfamiliar with Christian rituals. Outside of church, access to music was increasingly rare for commoners. Live performances became a luxury enjoyed by wealthy patrons, who could afford to hire a few select artists for private events. But by the 19th century, as the Industrial Revolution led to a burgeoning middle class, a new emphasis was placed on leisure, and public concerts regained their importance. In an effort to capitalize on this, German composer Richard Wagner decided to start the Bayreuth Festival in Germany, a musical event that produced large scale performances of his own work. One of Wagner’s most popular compositions at the festival was called The Ring Cycle, a masterpiece consisting of four separate operas.

Gina Arnold:

It became an instant hit. It’s still going today. There’s a waiting list of 10 to 15 years to get a ticket to see it. It’s a really longstanding and amazing thing, but really it’s very much the genesis of the idea of musicians taking over their own space and becoming basically rock stars.

Walter Isaacson:

These late 19th century festivals were still fairly small by today’s standards. After all, the music was acoustic and would be difficult to hear for many in attendance if the crowd was too big. But an important piece of 20th century technology would solve this problem and help create the foundation for the large-scale modern music festival.

Gina Arnold:

The amplifier sort of changed everything in terms of anything that involved sound. So it was invented in about 1912. Obviously, it amplified the human voice, so notably radio, television and movies, but after World War II, it got put into music. So all of those things are very sort of, I would call them early 20th century inventions, that changed music in America and in the world, and led to the invention of the music festival.

Walter Isaacson:

By the 1950s, amplifiers designed for musical instruments were adopted by many artists, and as live music became amplified, audiences at musical events grew in size. This set the stage for the first multi-day outdoor music festival in North America, the Newport Jazz Festival, in 1954.

Christian McBride:

The Newport Jazz Festival was started by two people, a woman by the name of Elaine Lorillard, a person who lived in Newport, who often frequented George Wein’s club, George Wein, who was known as basically the godfather of all music festivals. He had a jazz club in Boston for many years called Storyville.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Christian McBride. He’s the artistic director of the Newport Jazz Festival.

Christian McBride:

Miss Lorillard went into George’s club. They got to be friends, and she was a big jazz fan. And she said, “I would like to have a festival in the city where I live, which is Newport.” I think George, at that time, just thought, “Exactly what does that mean, a festival?” Because the American music festival did not exist before this conversation. So he decided that he would call on some of his friends, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and they would build a little stage and they would have this outdoor concert. It turned out to be one of the greatest ideas and one of the biggest hits in American culture.

Walter Isaacson:

Over the next few years, the Newport Festival got bigger and bigger, inspiring a jazz festival revolution that became the foundation for the big music festivals millions flock to today.

Christian McBride:

And then all of these jazz festivals that sort of followed suit, the Hampton Jazz Festival, the New Orleans Jazz Heritage Festival, they were all started by George. So the concept of a music festival, from Woodstock all the way through Coachella and today’s festivals, Burning Man, all that was taken from the first page of George Wein. The concept of having an outdoor site, hiring a production team, getting major sponsors, that was George Wein that started all of that.

Walter Isaacson:

And to this day, Newport is still considered the premier jazz festival in North America, if not the world.

Christian McBride:

Every jazz artist in the entire world still wants to play the Newport Jazz Festival. Still number one. I’m glad we were voted Best Jazz Festival by the readers of Jazz Times Magazine in 2021. We still mean something to the jazz community.

Walter Isaacson:

By the 1960s, jazz was still very popular, and Newport continued to draw sizable crowds, but a new style of music had started to capture the imagination of American youth, rock and roll. Bands like The Beatles, Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd sold thousands of albums and packed arenas, but rock and roll wasn’t just about the music. It was also a driving force behind the counterculture movement of the 1960s. The Vietnam War, the first war in history to be televised, was underway. Many Americans were angered and horrified by the gruesome images they saw on TV, so music festivals became a space where anti-war youth gathered to express themselves through music.

Joel Rosenman:

We didn’t have a clue about how to build a rock festival. Nobody in our group had ever done something like that.

Walter Isaacson:

In the late 1960s, Joel Rosenman, an out-of-work lawyer and musician, had recently built a state-of-the-art recording studio in Manhattan. This got the attention of two other musicians who were looking to build one of their own, but there was a major problem. They didn’t have the money to finance a studio.

Joel Rosenman:

So I proposed that if we did a concert and charged for tickets, we would make enough money to finance the building of the recording studio. They were resistant to a concert, because I think they had seen in the past how concerts can fall apart. I should have listened to them, in retrospect, but eventually I convinced them.

Walter Isaacson:

This idea for a concert would eventually transform into the iconic Woodstock Arts and Music Festival, but before it could, Rosenman and his new business partners had to do some research, and their first step was watching a film about a pioneering music festival that took place two years before, the Monterey Pop Festival. Located at the county fairgrounds in Monterey, California, Monterey Pop in 1967 was a seminal event in rock history. It featured the first major appearances by artists such as Jimi Hendrix and The Who. The documentary was the grand unveiling of hippy culture to a wider audience, and Rosenman found their message of peace and love appealing.

Joel Rosenman:

There were three things about that movie that we tried to replicate. One of them was great music. Another was a sizable crowd. There were 28,000 people at this festival, the largest folk rock festival up till that point, and there was a sense of warmth and peacefulness and community. You could feel it when you watched that movie.

Walter Isaacson:

But the path for Rosenman and his partners to make their epoch defining festival was anything but smooth. After losing the permit for their original site, they had only three weeks to rebuild Woodstock’s infrastructure at their Bethel location. Then three days before the start of the festival, Rosenman was forced to make an excruciating decision, finish the stage or finish the fence around the festival grounds to control attendance. By Wednesday morning, a decision had been made, but not by Rosenman.

Joel Rosenman:

Overnight, at least 30- to 50,000 people had arrived at the festival and were in front of the stage, camped there, to make sure that they got good seats. This was Wednesday morning, and I thought, “We’re certainly not going to go into that crowd and explain to them that they had to leave the festival to be readmitted on Friday as paying customers.”

Walter Isaacson:

The result was that Woodstock founders could no longer charge admission for the biggest concert in US history. And since fair is fair, they also refunded those who had already paid, so it’s easy to understand why The Who and the Grateful Dead wanted to make sure they got paid before they took the stage. Rosenman and his partners lost millions, but they had one last card to play.

Joel Rosenman:

And so we’re on the hook, and we stayed on the hook until a couple of months later when Warner Brothers, seeing what they had in maybe 400 cans of film that had been shot at the festival, approached us to buy those cans of film so that they could make a movie, like the movie about Monterey Pop turned out to be a blockbuster of a movie.

Walter Isaacson:

Their movie went on to win an Oscar, and after 10 years of residuals, the Woodstock founders finally broke even. To this day, Woodstock is synonymous with sixties hippie culture. Any mention of the festival conjures images of young people with flowers in their hair, dancing wildly in the mud. But the cultural importance of the event did not immediately result in a thriving festival industry.

Walter Isaacson:

In the years that followed, a slew of unsuccessful and occasionally disastrous attempts to recreate the magic of Woodstock led to a lull in music festivals. Then in 1991, a newly minted Lollapalooza reimagined festival culture into something that caught the attention of youth once again. Headliners included a diverse mix of artists, including Jane’s Addiction, Nine Inch Nails, Violent Femmes and Ice-T, but perhaps most importantly, Lollapalooza introduced festival goers to an experience that went beyond music. Tents displayed art pieces and virtual reality games while information tables raised awareness about different political and environmental issues. In doing so, Lollapalooza helped usher in a new brand of American music festivals, and today there are a few festivals as unique as the Coachella Valley Music Festival.

Stephen Lieberman:

Coachella is a great example of current day festival experiences, because it crosses the lines of so many various demographics and musical experiences.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Stephen Lieberman. He’s a renowned festival designer who’s programmed stages at events such as Lollapalooza, the Electric Daisy Festival, and Coachella. Lieberman got his start in the nightclub scene, working teen nights at his friend’s uncle’s club.

Stephen Lieberman:

So that led me down this path of where I am today. Back then, I wasn’t doing lighting and production. I didn’t know what that meant. I was cleaning glass, mopping the floors, and refilling juices and sodas for the bar. But that slowly turned into hanging out with the DJ, flipping light switches to the music, and really enjoying the environment and the experience of what nightlife meant, surrounding by pulsing lights and music and all of that that went with it. Who doesn’t love that?

Walter Isaacson:

Eventually Lieberman took that love and used it to start designing underground venues during the rave boom of the 1990s. But as law enforcement began to crack down on these illegal events, the trademark electronic dance music, lighting, and stage design of raves needed somewhere to go. So Lieberman and other ravers took their craft to the more legitimate stages of the reborn festival scene. In doing so, the unique immersive and sensory rich environments that Lieberman first built in the nineties are influencing the philosophy and design of today’s mega festivals. It’s this sensibility that Lieberman brings to Coachella’s Yuma stage, which he designs for the festival every year.

Stephen Lieberman:

What we do is we build this environment, and it’s not really a stage, although they might call it a stage. It’s a popup night club in the desert. So this year, for instance, we accommodate, I think our capacity is about 5,000 people. The liner of the tent is black, so you walk in there at two o’clock in the afternoon, and the door closes behind you, you’re in a blacked out nightclub. Then the lighting and production in there is a very over-the-top techno style design. What I mean by that is, it is very geometric, it’s very matrix oriented, with a lot of sharp edge details.

Walter Isaacson:

And it always includes a nod to Lieberman’s roots.

Stephen Lieberman:

You come into Yuma, and you are going to get some nostalgia of a dance music environment, nightclub environment, but you’re also going to get an in-your-face, over-the-top visual journey, this truly immersive environment.

Walter Isaacson:

Yuma is one of the oldest stages at Coachella, and across all its stages and experiences, Coachella is legendary for its use of the most innovative technology to enhance the festival goer’s experience. As far back as 2012, Coachella famously used VR and holographic tech to reunite the late rapper Tupac Shakur with Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre for an onstage performance that made headlines around the world. More recently, Coachella introduced augmented reality technology, transforming a stage into an interactive cosmic spectacle. Fans could use their smartphones to watch augmented visuals, like astronauts, planets, and space stations react in real time to musical performances. But for Lieberman, the thing that transcends the technology is inspired design.

Stephen Lieberman:

Special effects and lasers and flames and drones, and all the other fun toys that we get to play with, but all of these items and all of these milestones, whilst amazing, support ideas. That is really where the creatives are a critical part of this puzzle. We get to really push boundaries of what these experiences are, and very avant garde, very edgy design, and it’s a laboratory for experimenting with new ideas and concepts.

Walter Isaacson:

And as people like Lieberman continue to push boundaries of festival design, they’ve expanded the concept of what a festival can be.

Dede Flemming:

My definition of a festival, interestingly enough, music doesn’t stand out. It’s people gathering in whatever fashion, and it’s people connecting, and that’s I think an important one.

Walter Isaacson:

This is DeDe Flemming. DeDe and his twin brothers are the co-founders of Do LaB. Do LaB is a design company that builds installations, innovative structures, and immersive environments. They also produce the Lightning in a Bottle Festival, which began as a birthday party in the year 2000.

Dede Flemming:

We decided to throw a little mountain party with a hundred or so people, close friends, and that really just snowballed into a music festival. It was called Lightning in a Bottle, and we did it every year. Not meant to be a festival, but it grew slowly.

Walter Isaacson:

A smaller, independent festival, the main goal of Lightning in a Bottle is to bring together like-minded people to form a tight-knit community.

Dede Flemming:

Lightning in a Bottle, it’s kind of a living breathing thing, and it’s certainly not the same thing every time. Today it is a collection of music and art and interactivity, and we have workshops and classes, and a whole lifestyle component of it. Kids programming. There’s family programming. But the core of it still is, it is a party. Once the sun goes down and these lights come on and the music turns up, it’s undeniable. It is a party.

Walter Isaacson:

It also provided the perfect atmosphere for the artistic brothers to create the large-scale immersive art installations that has made Do LaB famous. Soon other festivals started to notice these art installations that were transforming Lightning in a Bottle into an interactive fantasy world.

Dede Flemming:

But really, from the beginning, we wanted to create experiences. The stage that we just created at Coachella we call Warrior One, that’s I think 300 feet by 300 feet. It’s just a massive, massive structure. It’s mostly cables holding up giant beams and poles, and the art is in the design. We have performers and aerialists that are rigged to the structure and do aerial. So we’ve always had that performance element that helps draw people in.

Walter Isaacson:

And as installations get more complex and festivals continue to expand, organizers are using technology to better understand how attendees navigate the grounds so they can improve the experience.

Dede Flemming:

Technology’s playing a huge part in festivals today. We use a lot of drone technology these days to capture our festival layout so that we can assess and understand the flow of people better, how we want to lay things out more strategically, but we use drones to really help show us where those movements are, where people congregate, and those people are going to tell you where they want to be, and we try and capture that for the next time.

Walter Isaacson:

Drones are also frequently coupled with RFID tracking technology. Attendees scan wristbands fitted with RFID chips as they move through the grounds, giving organizers unprecedented insights into which festival experiences and artists are most popular. But even as technology and festivals become more intertwined, the core of any music festival, the need for novel experience, great music, and human connection is the same as it was during Woodstock in the summer of 1969 and centuries before in ancient Greece.

Dede Flemming:

If I were to take a stab at what the common denominator is with festivals since the beginning of time, I’m going to say like-minded community. I think that’s the number one ingredient. I think they’re the ones that prove to be most successful and have longevity, because it’s not about the artist that’s on stage or the hottest DJ or whatever it is, or the biggest technology. It’s the people. You want to come back because you’re with people that are like you and share the same outlook or ethos or whatever it is. So the biggest common denominator is people and community that is created around these gatherings.

Walter Isaacson:

I’m Walter Isaacson, and you’ve been listened to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies, who believe there’s an innovator in all of us. If you’d like to learn more about the guests on today’s episode, please visit delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

Over four days in 1969, more than half a million people gathered on a dairy farm in Bethel, New York for what would become known as one of the most legendary music festivals of all time—Woodstock. Though Woodstock helped give rise to a thriving industry and cement the music festival as an important part of North American culture, festivals have brought people together since ancient times. The ruins of stone arenas in Greece, Italy, Turkey and other places give us insight into early festivals and the engineering behind them.

Over four days in 1969, more than half a million people gathered on a dairy farm in Bethel, New York for what would become known as one of the most legendary music festivals of all time—Woodstock. Though Woodstock helped give rise to a thriving industry and cement the music festival as an important part of North American culture, festivals have brought people together since ancient times. The ruins of stone arenas in Greece, Italy, Turkey and other places give us insight into early festivals and the engineering behind them. Gina Arnold

is a former rock critic, writer, and academic who studies live performance and music festivals. She holds a Ph.D. in cultural studies and is the author of the book "Half a Million Strong: Crowds and Power from Woodstock to Coachella."

Gina Arnold

is a former rock critic, writer, and academic who studies live performance and music festivals. She holds a Ph.D. in cultural studies and is the author of the book "Half a Million Strong: Crowds and Power from Woodstock to Coachella."

Christian McBride

is an eight-time Grammy-winning bassist, composer, bandleader, and educator. He is the Artistic Director of the historic Newport Jazz Festival, the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, the TD James Moody Jazz Festival, and the National Jazz Museum in Harlem. In addition to artistic directing and touring with his ensembles, he hosts radio shows on NPR and SiriusXM.

Christian McBride

is an eight-time Grammy-winning bassist, composer, bandleader, and educator. He is the Artistic Director of the historic Newport Jazz Festival, the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, the TD James Moody Jazz Festival, and the National Jazz Museum in Harlem. In addition to artistic directing and touring with his ensembles, he hosts radio shows on NPR and SiriusXM.

Joel Rosenman

is Managing Director of Woodstock Ventures. In 1969 he turned a bad idea, to build a one-room recording studio in the woods of upstate NY, into a better bad idea: the Woodstock Festival. The rest, as they say, is history – 50 years of exploring how to implement what happened during that extraordinary weekend into what is happening today.

Joel Rosenman

is Managing Director of Woodstock Ventures. In 1969 he turned a bad idea, to build a one-room recording studio in the woods of upstate NY, into a better bad idea: the Woodstock Festival. The rest, as they say, is history – 50 years of exploring how to implement what happened during that extraordinary weekend into what is happening today.

Dede Flemming

is the co-founder of Do Lab, a company that builds art installations, innovative structures and immersive environments. Dede has also been instrumental in the planning, execution and growth of the Lightning In A Bottle festival and Coachella’s beloved stage, the Do LaB Stage.

Dede Flemming

is the co-founder of Do Lab, a company that builds art installations, innovative structures and immersive environments. Dede has also been instrumental in the planning, execution and growth of the Lightning In A Bottle festival and Coachella’s beloved stage, the Do LaB Stage.