Walter Isaacson:

Imagine for a moment that you are a sailor in the British Navy, during the 18th century. You’re about to embark on your first voyage and you’re nervous that this might be the last time you’ll ever see the shores of England. You’ll almost certainly encounter violent storms on your journey that could potentially destroy your ship. It’s also possible that you’ll be killed by enemy fire. But there is another, perhaps even more agonizing and certainly more likely cause for your demise, disease.

In one expedition to the Pacific Ocean, in the 1740s, 1,300 sailors out of an original compliment of 2,000, were lost to disease Z. The biggest killer was scurvy, a horrific illness whose symptoms include bleeding gums, severe joint pain, fatigue, and depression. At the time, the cause of scurvy was not well understood and there was no cure. Sailors were encouraged to drink a quart of cider or a day or half a pint of sea water or eat two oranges and one lemon. Sometimes, patients got better, but most of the time they didn’t. And a Scottish doctor, named James Lind, was determined to find out why.

In 1747, Lind joined the Royal Navy as a surgeons mate and was invited aboard the HMS Salisbury to try to find a cure for scurvy. He began by conducting a controlled clinical trial. He took 12 men who were suffering from the disease and divided them into six pairs. Each pair was offered one of the standard treatments, and Dr. Lind recorded the results. By the end of the first week, it was clear that the patients who were prescribed oranges and lemons were doing better than others in the trial. Lind had found what he believed to be a clear link between the consumption of citrus fruits and the improvement in the sailor’s condition. Six years later, he published the first edition of his Treatise of the Scurvy.

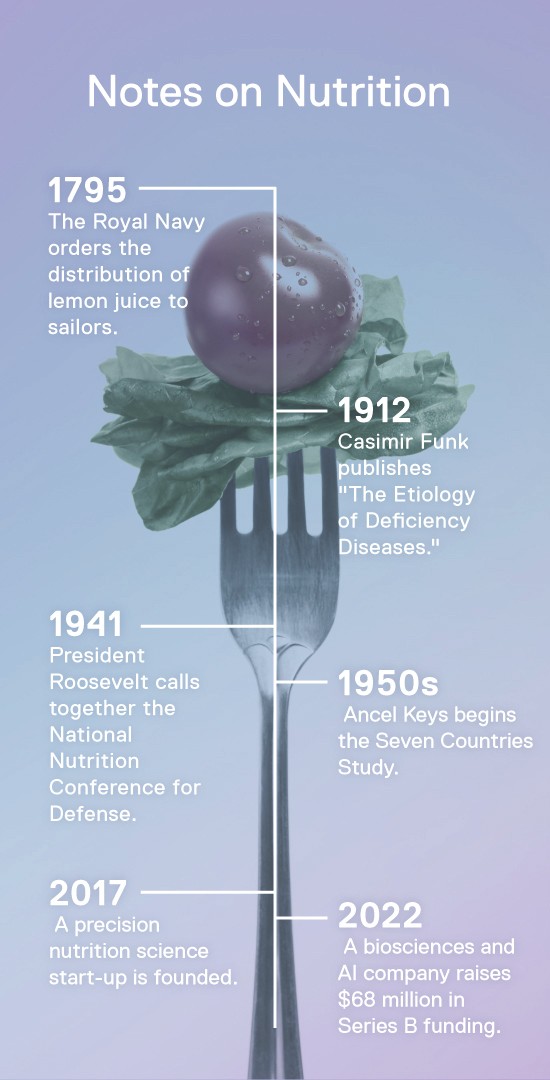

But it wasn’t until 1795, nearly 50 years after his initial experiments, that the Royal Navy finally ordered the distribution of lemon juice to sailors. And it wasn’t until 1928 that researchers identified ascorbic acid, or vitamin C, as a critical ingredient in citrus fruits that prevents scurvy.

Although it took decades before the world understood what he discovered, James Lind is now recognized as a trailblazer in promoting the healing power of plants and the importance of nutrition as preventative medicine. Today, we know much more about how our diet affects our health. And the news isn’t good. Globally, it’s estimated that unhealthy diets are responsible for more than 11 million preventable deaths every year. That’s more than any other risk factor, including smoking. Scientists now recognize that lowering healthcare costs and increasing life expectancy can happen only with better nutrition. Many also believe that one of the keys to a healthier diet lies in eating more food derived from plants, just as James Lind discovered more than 200 years ago.

I’m Walter Isaacson and you’re listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Speaker 2:

Hot dogs, hamburgers, ice cream and cake.

Speaker 3:

Just what do you kids like to eat best.

Speaker 4:

Here is a chart of the seven groups of food.

Speaker 5:

Those are the foods you should eat every day if you want to be healthy.

Speaker 6:

The best way naturally is to [inaudible 00:04:46] vitamins in food.

Speaker 7:

Everything tastes good and you’re eating well.

Walter Isaacson:

The connection between good food and good health was first made way back in the fourth century BC by Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine. Hippocrates is often quoted as saying, “Let thy food be thy medicine and thy medicine be thy food.” The Hippocratic Oath, still administered to graduating physicians today, includes the line, “I will apply dietetic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment.”

But what are those dietetic or dietary measures? For most of human history, our main preoccupation was finding enough food to survive. And while starvation is still a serious problem in many parts of the world, people in wealthier nations are dying because they’re eating too much of the wrong food. It’s leading to an epidemic of heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic diseases.

Dariush Mozaffarian:

Well, I certainly think that all doctors understand that poor nutrition is one of the biggest causes, if not the single biggest cause of poor health. They don’t know what to do about it.

Walter Isaacson:

Dariush Mozaffarian is a professor of nutrition and medicine at Tufts University in Boston.

Dariush Mozaffarian:

There’s a lot of research that shows that. If you ask doctors, 80, 90% of them say nutrition is one of the biggest issues facing their patients, and 80, 90% of them say they wish they knew more and had enough training to deal with it.

Walter Isaacson:

For a long time, doctors receive little nutritional training in medical school, partly because so little was known about the exact relationship between food and disease. That began to change in the latter part of the 19th century. One of the first breakthroughs was the discovery of vitamins. In 1888, a young Dutch doctor named Christiaan Eijkman was sent to Indonesia by the Dutch East India Company to study an outbreak of beriberi. Beriberi is a painful and deadly disease, was symptoms that closely resembled scurvy.

Dariush Mozaffarian:

And his breakthrough was not studying people, but studying chickens. So he just noticed just by chance, that the chickens developed beriberi one year. And when he looked to see what happened, he found that the normal shipment of cheap brown rice had been delayed. And so the cook had given them the white rice, which was more expensive for people, and all the chickens got beriberi. And when they gave them the brown rice, their beriberi improved. Now, Eijkman didn’t fully understand what happened. He thought that the rice held some kind of poison and that the brown color, the bran over the rice held the antidote to the poison. That was his theory.

Walter Isaacson:

Eijkman’s theory was actually wrong. There was no poison in the rice. But his work was critical in our understanding that food contained essential chemical compounds that our bodies couldn’t make. And the absence of those chemicals could make us sick. We now know that the reason the chickens became ill when eating the white rice is that there’s a compound, or amine found in the husk of brown rice that prevents beriberi. That compound is thiamine, or vitamin B1. When the husks were removed to produce white rice, it eliminated the thiamine and the chickens became ill. The discovery of this amine was made about a decade later by a Polish American scientist named Casimir Funk, who built upon Eijkman’s work and introduced two important new words in our nutritional vocabulary.

Dariush Mozaffarian:

And so he published a paper in 1912 called The Etiology of Deficiency Diseases. That’s the first time the word deficiency diseases had been used. And he recognized that it was an amine in chemistry, and he said, this is a vital amine for health. And so that term vital amine was shortened to vitamine. And now we of course, have dropped the E to call it vitamin. So he also coined the term vitamin. And so Casimir Funk really was the one that identified that there are nutrients in food that our bodies can’t make that we need. And then really, it wasn’t until 1932 that the very first vitamin was isolated and synthesized. And so this discovery in 1932 of vitamin C being synthesized, really, you could actually prove directly that if you took that vitamin away, you caused scurvy, and if you gave it back, you cured scurvy. And so this led to this explosion of nutrition science from the 1930s into the 1950s where basically, every major vitamin and its effects on health were discovered.

Walter Isaacson:

By the 1930s, deficiency diseases had become a major focus for researchers. The idea that you could get sick because of something you didn’t have in your body overturned conventional wisdom. Scientists began to link specific deficiencies with their diseases and develop synthetic vitamins to solve the problems. Vitamin C for scurvy, vitamin B1, or thiamine, for beriberi, and vitamin D for Rickets.

At the same time, in the US, millions were experiencing hunger and malnutrition during the Great Depression. President Franklin Roosevelt was concerned that if America was called upon to go to war, there might not be enough healthy, well-nourished soldiers to do the job. So in May, 1941, he brought together more than 800 scientists for a gathering called the National Nutrition Conference for Defense. The conference produced the first ever recommended daily allowances for calories, proteins, and vitamins. Manufacturers responded by adding vitamins to everyday foods like bread and milk, and launching a massive ad campaign to convince consumers to buy vitamin supplements. And scientists began taking a closer look at the connection between food and disease. One of the most important and controversial of these early researchers was an American physiologist, named Ancel Keys.

Marion Nestle:

I was blown away when I first began looking at what Ancel Keys had done. He was a giant.

Walter Isaacson:

That’s Marion Nestle, who is herself a giant in the field of nutrition. She’s a Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies and Public Health at New York University, and the author of dozens of books and articles about food and nutrition. Ancel Keys’ rise to fame rested on a pioneering multi-country study of diets and health.

Marion Nestle:

He did the Seven Countries Study, which was the early, early, early epidemiology in which he went into seven countries and looked at diet and correlated it with heart disease risk and found the first early correlations of what people were eating with their risk of coronary heart disease.

Walter Isaacson:

Keys’ Seven Countries Study was widely heralded and it landed him on the cover of Time Magazine in January, 1961. Two of his most important conclusions still resonate today. The first was that there appeared to be a correlation between countries where people consume what was called a Mediterranean diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, pasta and olive oil, low in meat, fish and dairy products have a lower rate of heart disease. That finding is still widely accepted. His second conclusion has proven to be more controversial.

Marion Nestle:

And he came up with the idea that high fat diets were very closely correlated with a heart disease risk. And now I look back and I think he should have been paying more attention to calories, in general. But the studies were extraordinary for the time, and he did them the best he could at the time. And I think much respect needs to be paid.

Walter Isaacson:

But not a lot of respect is paid to Ancel Keys today. He remains a polarizing figure in the nutrition world. Many experts believe his conclusion linking a high fat diet to heart disease may not have been totally wrong, but it was overly simplistic and help lead Americans down a dangerous path. By the 1980s, physicians were preaching the gospel of low fat diets to their patients to prevent heart disease and promote weight loss. Manufacturers were filling grocery store shelves with low fat, highly processed versions of everyday food with calories that came from sugar and refined carbohydrates. The result was precisely the opposite of what was intended. Americans kept getting sicker and their waistlines continued to expand. At the same time, there was also a big increase in the American food supply and the food industry had to figure out a way to sell all of it to consumers.

Marion Nestle:

For example, portion sizes got larger. All these studies sponsored by the food industry started coming out saying that if you ate multiple meals, small meals a day, you would be able to protect yourself against gaining weight. When in fact, the more times a day you eat, the more calories you take in. So I think a lot of things happened at once as part of the food industry’s need to maintain profits at a time when it was very, very competitive.

Walter Isaacson:

The low fat craze was in full swing when Dariush Mozaffarian began his career as a cardiologist in Boston in the 1980s. Nutrition wasn’t really on his radar, until he began to realize that poor diet was a big reason why so many of his patients were suffering from high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity. And while the food industry was clearly a problem, so two were nutrition scientists. Mozaffarian believes they were taking a misguided reductionist approach to nutrition. They were searching for a single dietary cause for disease or a single nutrient that might prevent it.

Dariush Mozaffarian:

So that led to fairly oversimplified science where saturated fat became the cause of heart disease or total fat became the problem for heart disease or for breast cancer, which it was also thought was a cause of breast cancer. And so that led to very simplistic dietary recommendations, let’s avoid fat and avoid saturated fat because we can fix those problems by doing that. And so that work in the 1980s and 1990s led to the low fat diet hypothesis. What we’ve learned since in just the last 20 years is that nutrition science for complex, chronic long-term diseases, like heart disease, stroke, cancer, gut health, brain health and so on, this single nutrient, single disease idea breaks down completely and just doesn’t work.

Walter Isaacson:

And there is one prominent scientist who understood, earlier than most, that something wasn’t right. With these mainstream and overly simplistic beliefs about nutrition.

Dr. T. Colin Campbell:

I could see that nutrition seemed to be more important than one nutrient at a time. I finally, after being involved in this field for so long in different ways, I come to realize that gosh, these things work together in marvelous ways if we eat the right food. That’s all we need to do is eat the right food.

Walter Isaacson:

Dr. T. Colin Campbell hasn’t always eaten the right food. He was born on a dairy farm in 1934 and spent his youth and early adulthood eating a diet loaded with animal protein. He trained as a biochemist in university and in the 1960s went on a research trip to the Philippines to look at malnutrition in children. The assumption was that those children needed to consume more animal protein. But what he discovered was that those who ate the most meat were more likely to develop liver cancer.

Dr. T. Colin Campbell:

And so that was a puzzle. Does animal protein increase cancer? So I came back home and got funding from our government, National Institutes of Health, to start a research program that then continued for years. And initially, it was simply asking this question, “Is it true that animal protein increases cancer?” That sounds ridiculous. And the eureka moment came not too long after when I found out in the experiment animal studies, animal protein turns on cancer and it does it quickly. It’s a very sensitive and remarkable response, at least in the cancer we were working with. We could turn cancer on and off just by changing the diet. That was the eureka moment.

Walter Isaacson:

Since that eureka moment 50 years ago, Campbell has been on a crusade and it’s often been a lonely one. He’s now a professor emeritus at Cornell and the author of more than 300 research papers and five best selling books. But at a time when the consensus was that animal protein was superior to plant protein, his idea for a diet that consisted exclusively of whole unprocessed foods derived from vegetables, fruits, grains, and legumes was widely criticized. And while his particular version of a plant-based diet, a term that he coined in the 1970s, might seem a bit extreme, his once heretical ideas about the value of incorporating more plants into our diets have become mainstream. And to a large degree, that’s because we now know so much more about why plants are good at keeping us alive.

Lee Chae:

I think of today, when we think of plants, particularly in terms of food, people think of calories, or they think of protein. And my argument to the world is that, that is a very base way to think about plants.

Walter Isaacson:

That’s Lee Chae. He’s the co-founder and chief technology officer of a company called Brightseed. Brightseed identifies bioactive compounds in plants and their potential uses for preventing and treating a whole range of diseases. It turns out that plants are incredibly complex. Their genomes are actually larger than the human genome, and they produce a staggering array of bioactive compounds. But we only know the identity of about 1% of these compounds. The others of what Chae calls the dark matter of the plant kingdom. He hopes that Brightseed can increase that number from 1% to 80% over the next few years. Brightseed plans to do this by using genetic sequencing and artificial intelligence to get a handle on what’s actually going on inside plants.

Lee Chae:

So we started with what is the issue out there in the world that we want to address? And right now we know that 80% of healthcare spend is spent on chronic disease and it’s getting to the state where no government can afford that, no employer, no insurance company, certainly not any consumer can afford the price tags that are coming with the rising incidence of chronic disease. And the maddening thing or the opportunity here is that 80% of chronic disease is preventable through diet and lifestyle. So the idea is can we form a deep data set around these bioactive and plants where what plants you can find them in that will allow people access to these solutions before they get to a disease state?

Walter Isaacson:

Brightseed is already beginning to apply its technology to real life health problems. It’s starting with the estimated two billion people in the world suffering from too much fat on their livers. Fatty liver disease is mostly caused by bad diet and there are no drugs to treat it. Brightseed used its AI to identify two compounds that could actually prevent fat from binding to the liver, and then look for plants where those compounds might be found.

Lee Chae:

What’s interesting is that over about 400 different plant species can produce it. We have tested in the lab about 80 different plant species that that can produce it. And one of the plant species that’s a really good producer of it is black pepper. So black pepper, which is well studied for antioxidant anti-inflammation properties for centuries, here is a compound that’s been sitting under our nose that has this biological activity. And this bioactive had never been seen before in a very well studied traditional medicine. And that’s the power of bringing the approach of enlarging that window from 1% to 20 to 50 is that, hey, there is a real chemical molecular basis to health effects. And when we enlarge that window, we’re going to find more opportunities to help people.

Walter Isaacson:

Brightseed’s work with bioactive compounds is still at a very early stage. The hope is that one day it will be able to identify millions of bioactives that exist within the plant kingdom, discover what they might be good for, and produce a map of the plants where they could be found. None of this would’ve been possible without the enormous advances in computing power that have allowed plant and human genomes to be sequenced. And those advances have helped jumpstart a whole new approach to nutrition that is focused less on calories and fat and more on what happens to our food when it enters our gut microbiome.

Tim Spector:

It’s really a whole new organ in our bodies that we’ve not really considered fully before. We’ve seen it as an enemy rather than as a friend.

Walter Isaacson:

Tim Spector is a professor of genetic epidemiology at King’s College in London.

Tim Spector:

And it’s this real insight into suddenly, there’s this new organ body that interacts with the food we eat and the diseases and aging, et cetera that we are all subject to.

Walter Isaacson:

Every time we eat, we’re feeding a vast army of about 100 trillion microbes that live inside our gut. They transform our food into the enzymes, hormones, vitamins and other metabolites that affect everything about our mental and physical health. They also impact how much weight we gain and our chances of developing chronic diseases. Spector’s research began in the 1990s in the UK with a massive study of identical and non-identical twins. About 10 years ago, that research took a big step forward with the development of technology that allowed for the full genetic sequencing of every microbe in our gut. Spector used that technology to try to answer a perplexing question, “Why didn’t identical twins who share virtually the same DNA get the same diseases?” The answer turned out to be that their genes did not matter as much as the microbes in their gut, and they were actually quite different.

Tim Spector:

They only share less than around 30% of those microbes with each other. We’re all incredibly individual. So given that these microbes are producing chemicals, they are basically like little mini pharmacies, it makes sense that this could be the reason that identical twins get different diseases and why all of us are much more different in our response to our environment than we’ve believed to this moment and why we need to think of about food and nutrition in a very different way to the traditional one.

Walter Isaacson:

Spector tested his hypothesis that no two microbiomes are the same, by giving identical meals to 1,000 people and seeing how their bodies reacted.

Tim Spector:

The range of differences between people was much bigger than we thought. It was a tenfold difference in normal people’s response to an identical breakfast muffin, for example, in terms of how much their sugar peak, how high that got, how quickly it disappeared, and how their fat levels came and went in the blood. That was amazing. And in fact, it wasn’t very genetic at all. Also meant that you could do something about it by changing advice, by changing the microbiome.

Walter Isaacson:

If no two microbiomes are the same, then it makes sense that no two diets should be the same either. Once you discover what’s going on with the microbes in your gut, you can tailor your diet accordingly. In 2017, Spector co-founded his company ZOE, to put this new research about the gut microbiome to work. His company is a pioneer in the growing field of precision new nutrition. Spector’s clients receive a microbiome collection kit and a standardized menu that they follow for several weeks.

Tim Spector:

You see you’re recording what you are doing, you’re logging your food. Then that’ll get shipped back and a few weeks later you get your results. And on your phone, you’ll get a way to look up any food you want to eat. It gets you a score and you can then, from 0 to 100, which will be personalized to you. So a mixture of these scores of your sugar response, your fat response, and your microbiome. So then you’re starting to pick foods, regardless of calorie or whatever that you like, giving you less of a sugar peak, less of a fat peak, and are better for your gut microbes.

Walter Isaacson:

Spector is a big fan of the Mediterranean diet, but the joy of precision nutrition is that no food is off limits, provided it doesn’t interfere with your gut health. He believes that eventually, measuring your gut biome will be as routine and affordable as measuring your blood pressure. But we’re still long way from that point.

In the meantime, figuring out what you should or should not eat can be confusing. There’s a lot of conflicting advice out there, which is why the best bet might be to follow the seven words of wisdom of a claimed food writer, Michael Pollan. He summarized his key to healthy eating this way, “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.”

I’m Walter Isaacson and you’ve been listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies, who believe there’s an innovator in all of us. If you’d like to learn more about the guests in today’s episode, please visit delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

Dariush Mozaffarian

is a cardiologist, Special Advisor to the Provost, Dean for Policy, and Jean Mayer Professor at the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy. He is also Professor of Medicine at Tufts School of Medicine.

Dariush Mozaffarian

is a cardiologist, Special Advisor to the Provost, Dean for Policy, and Jean Mayer Professor at the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy. He is also Professor of Medicine at Tufts School of Medicine.

Marion Nestle

is Paulette Goddard Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health, Emerita, at New York University, in the department she chaired from 1988-2003 and from which she retired in September 2017. She writes books about the politics of food, most recently a memoir, Slow Cooked: An Unexpected Life in Food Politics. She blogs daily (almost) at foodpolitics.com.

Marion Nestle

is Paulette Goddard Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health, Emerita, at New York University, in the department she chaired from 1988-2003 and from which she retired in September 2017. She writes books about the politics of food, most recently a memoir, Slow Cooked: An Unexpected Life in Food Politics. She blogs daily (almost) at foodpolitics.com.

T. Colin Campbell PhD

has been dedicated to the science of human health for more than 60 years. His primary focus is on the association between diet and disease, particularly cancer. Dr. Campbell is largely known for the China Study--one of the most comprehensive studies of health and nutrition ever conducted but his profound impact also includes extensive involvement in education, public policy, and laboratory research.

T. Colin Campbell PhD

has been dedicated to the science of human health for more than 60 years. His primary focus is on the association between diet and disease, particularly cancer. Dr. Campbell is largely known for the China Study--one of the most comprehensive studies of health and nutrition ever conducted but his profound impact also includes extensive involvement in education, public policy, and laboratory research.

Tim Spector

is a Professor of Epidemiology and Director of the TwinsUK Registry at King’s College London. His current work focuses on the microbiome and nutrition, and he is co-founder of ZOE, a personalized nutrition company, which runs the world’s largest nutrition study, ZOE Predict and has created a commercial at-home kit for personalized nutrition.

Tim Spector

is a Professor of Epidemiology and Director of the TwinsUK Registry at King’s College London. His current work focuses on the microbiome and nutrition, and he is co-founder of ZOE, a personalized nutrition company, which runs the world’s largest nutrition study, ZOE Predict and has created a commercial at-home kit for personalized nutrition.

Lee Chae, Ph.D

is co-founder and Chief Technology Officer of Brightseed, a company pioneering the discovery of plant-based bioactives for health with an advanced AI platform named Forager.

Lee Chae, Ph.D

is co-founder and Chief Technology Officer of Brightseed, a company pioneering the discovery of plant-based bioactives for health with an advanced AI platform named Forager.