There are telltale signs of the impact of climate change on the fish and seafood industry. This fall, for the first time ever, Alaska nixed its snow crab season because of a paucity of the creatures in the warming Bering Sea, and the amount of fish stocks within “biologically sustainable levels” has dropped from 90% in 1974 to 66% today.

“Climate change is putting stress on all of our food systems,” Dr. Michael Rubino, senior advisor for seafood strategy at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries, says on the agency’s Dive In podcast. “In some places, fish stocks are in decline because of changing composition or temperature or alkalinity of the water.”

Cue the robots

In Japan, fishermen have long used ike jime, a labor-intensive method of fish harvesting, to help ensure a catch stays fresher, longer. Under the technique, fish are quickly killed using a spike to the head. The procedure helps reduce the chance of a build-up of lactic acid and cortisol in the body of the fish—the presence of which can harm flavor and result in the fish being tossed.

Start-up Shinkei Systems has developed a robotic-based tool to automate this technique—claiming to result in a higher yield of fish that remain fresher after being caught and are, therefore, more likely to make it to the table. Used with striped bass, steelhead trout, black sea bass and certain other North Atlantic species, the robotic tool allows for the hands-on method to scale up and work more precisely to target the right fish. The refrigerator-sized device can process each fish in 10 to 15 seconds by mimicking the traditional hands-on method: Once the fish enter the machine, a computer-vision tool recognizes the species, finds its brain and other organs, and quickly kills it, ike jime-style.

“Ike jime is a proactive step to multiply the shelf-life of fish,” says Shinkei Systems co-founder Saif Khawaja.

Shinkei has launched pilot projects using its robotic device with fish farms in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and New York. “We envision every fish will eventually be ike jime’d so they last longer, taste better and contribute to more mindful handling of our fish,” Khawaja says.

Are geo-targeted fish farms the future?

As water temperatures rise and fish stocks thin, aquaculture—or fish farming—is likely to play an ever bigger role. The U.S. imports two-thirds or more of the seafood eaten here and that half of the imported product comes from fish farms—not directly caught at sea.

At the federal level, NOAA Fisheries is promoting domestic aquaculture as a tool to address supply chain issues and safety concerns and to encourage sustainable seafood consumption. With federal nutrition guidelines recommending Americans double their seafood intake to twice a week on average, the supply also must increase to meet potential demand.

“Where is all that seafood going to come from?” Rubino says. “We can continue to import more and more seafood largely from aquaculture, or we can grow more of it here.”

However, increasing domestic production faces multiple hurdles. According to Rubino, aside from catfish, crawfish and some oyster farming, Americans “haven’t really embraced seafood farming.” This is due to a lack of awareness that so much seafood comes from farms. There are also other factors impacting production, like competing uses such as tourism, recreation, shipping, and energy.

“You think of the ocean as a big place. But especially in coastal areas, it’s pretty crowded,” Marino says.

NOAA has launched a spatial mapping technology called Ocean Reports that, when provided with a location in the U.S. ocean, in two seconds can tabulate “thousands, and thousands and thousands of data layers” about how humans use it, as well as its geochemical and biological features. The tool is meant to help streamline the lengthy process of engaging with stakeholders and reviewing projects for environmental impact.

We can continue to import more and more seafood largely from aquaculture, or we can grow more of it here.

—Michael Rubino, senior advisor for seafood strategy, NOAA Fisheries

“You still have to do a review of that particular project,” Rubino says. “The idea is that it would take a lot less time and energy and money to do it project by project when you’ve done it for the area as a whole up front.”

There’s an app for better-quality shrimp

In Vietnam, thousands of small, family-owned farms harvest tons of shrimp every year for export to the U.S. and other markets. However, Seafood Watch, a program of the Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, Calif., rates 71% of all farmed shrimp, and 86% of the product from Vietnam, as something for consumers to “avoid” because of disease outbreaks and chemical use. Yet, Vietnam is the third-biggest farmed shrimp producer globally and a major source of the product in the U.S.

To help ensure a healthier source of farmed shrimp, Seafood Watch has created a digital app called the Improvement Verification Platform (IVP). The app allows for a collaborative approach to uploading farm-level data via a tablet or smartphone and provides an instant determination of whether a farm is following best practices for sustainability. If not, the app will offer ways for it to improve.

By 2025, the goal of the IVP is for 20,000 giant tiger prawn farms in Vietnam’s Cà Mau province to receive Seafood Watch’s “Best Choice” or “Good Alternative” rating. By 2030, they aspire for the remaining farms to comply, as well.

A sea change in the works

Seafood Watch’s partnerships with shrimp and other fish suppliers are part of a multi-pronged strategy that includes consumer guides to check the sustainability of fish and seafood; support for seafood restaurants and businesses, including a Red-Yellow-Green color-coded system to rate the safety of fish and seafood; and a data-driven Social Risk Tool that helps businesses evaluate the risk of fish and seafood products based on over 80 indicators, including “publicly available evidence of forced labor, human trafficking and hazardous child labor abuses” in seafood supply chains.

“Our approach to pushing for sustainable seafood progress is both bottom-up and top-down,” says Erin Hudson, Seafood Watch program director. “The impetus for change can certainly come from the demand of the masses. It can also originate from industry wanting to meet those consumer demands, but often this is coupled by industry espousing the benefits of sustainability. Both simultaneously drive this work. Policy plays a role, too.” This combination of nurture—and nature—offers a potential win-win for both consumers and the world around us.

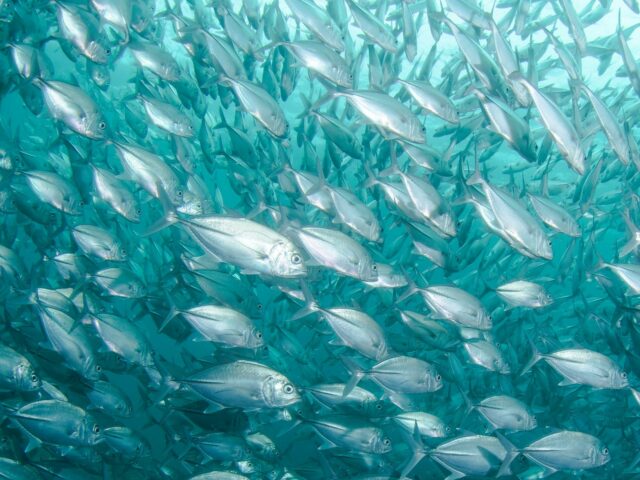

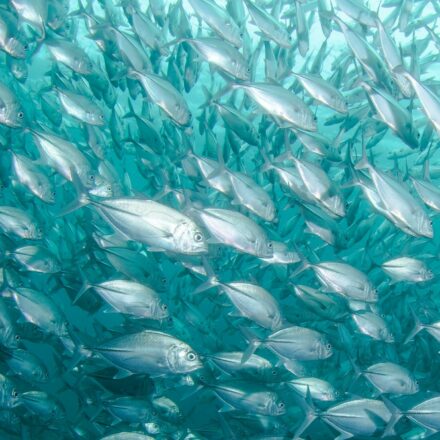

Lead photo of a school of tuna fish courtesy of Jean Wimmerlin/Unsplash.

Chances are the “fresh” catch at your local fish counter got there with a tech assist. Facing the twin headwinds of climate change and sustainability, the fish and seafood industry is using research-driven tactics and emerging technologies to improve—and maximize—their catch.

Today, robots are harvesting tuna in Maine, shrimp farmers in Vietnam are tapping an app to improve the sustainability of their product, and U.S. government scientists are deploying mapping technology to locate the next domestic fish farm. These efforts are part of a growing commitment on the part of the private and public sectors to make sure your next sushi roll or plate of shrimp scampi will be good for you—and the environment.