Walter Isaacson:

It’s February 13th, 1806, and Boston native Frederick Tudor is standing on the bow of his ship, the favorite, which is just launched into the Atlantic Ocean. He’s embarking on a five week journey to the Caribbean island of Martinique with cargo so precious he’s certain it will change the lives of the Martinique people forever. But that will only happen if his cargo can survive the perilous journey south. A journey known for its tropical storms and pirates, but these dangers are not what have Tudor pacing his deck with worry. His concern is the equator, or perhaps it’ll be more accurate, his ship’s proximity to it. Because Frederick Tudor’s cargo isn’t essential weaponry, lifesaving medicine, or even precious textiles. He’s shipping ice.

A year before this excursion Tudor had a crazy idea. He believed he could make a fortune by selling ice to people in tropical climates. But in the early 19th century, that’s no simple task. Refrigeration technology is still decades away from development, but Tudor believes he knows how to effectively transport his delicate cargo. Every winter Tudor’s family harvests ice from a frozen pond in Massachusetts and stores it in their ice house, cutting large pieces of ice, wrapping it in straw and storing it in a dark cool place has proven effective in minimizing ice melt when the weather warms. This allows them to enjoy one of their favorite treats deep into the summer, ice cream. It’s a treat he’s certain will have global appeal guaranteeing his success in the ice business. Most think that the 23 year old Tudor’s new venture is a fool’s errand, but he processes. So Tudor fills this ship full of ice and set sail.

Once in Martinique he plans to meet his brother who’s gone ahead to build the necessary ice house. Unfortunately for Tudor, his brother isn’t the most reliable business partner. When Tudor arrives, he discovers that his brother never built the ice house, leaving him stuck in Martinique with a shipload of melting ice. But Tudor is undeterred, he contacts a local restaurateur and says, “Let’s make some ice cream.” The restaurateur is skeptical, but his curiosity gets the better of him. Just as Tudor predicted, the people of Martinique could not get enough of this new cool, tasty dessert.

In the end, after much of his cargo melted, Tudor lost the equivalent to what would today be worth about $90,000. Sadly, his next several expeditions were even more disastrous. But as new methods for shipping ice were perfected, Tudor was eventually transporting 100,000 tons of ice per year. Suddenly ice cream became a treat anyone could make regardless of where they lived. By the age of 80, Tudor died with a fortune of $200 million. Today he’s credited with changing the very nature of how many cultures eat and drink, along with kick starting the world’s love affair with ice cream. It’s an industry now worth $113 billion with the average American eating 20 pounds or four gallons of ice cream every year.

I’m Walter Isaacson and this is Trailblazers. An original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Speaker 2:

If we wanted ice cream, I turned the crank.

Nearly 200 different flavors of ice cream have been developed.

Delicious flavor your whole family will prefer.

Making ice cream was usually a family event. So the journey of ice cream from Farm to Family continues.

Walter Isaacson:

Ice cream is one of the most complex food products you’ll ever consume. It’s an icy treat that contains all three states of matter at the same time: solids, liquids, and gas. But the path to discovering and perfecting this miraculous dessert began with a simple desire to keep things cold.

Jeri Quinzio:

They wanted to freeze other substances, and just putting something on ice doesn’t freeze it.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Jeri Quinzio, author of The Book of Sugar and Snow, a history of ice cream making.

Jeri Quinzio:

So the trick was, what do you do to make that ice freeze another substance?

Walter Isaacson:

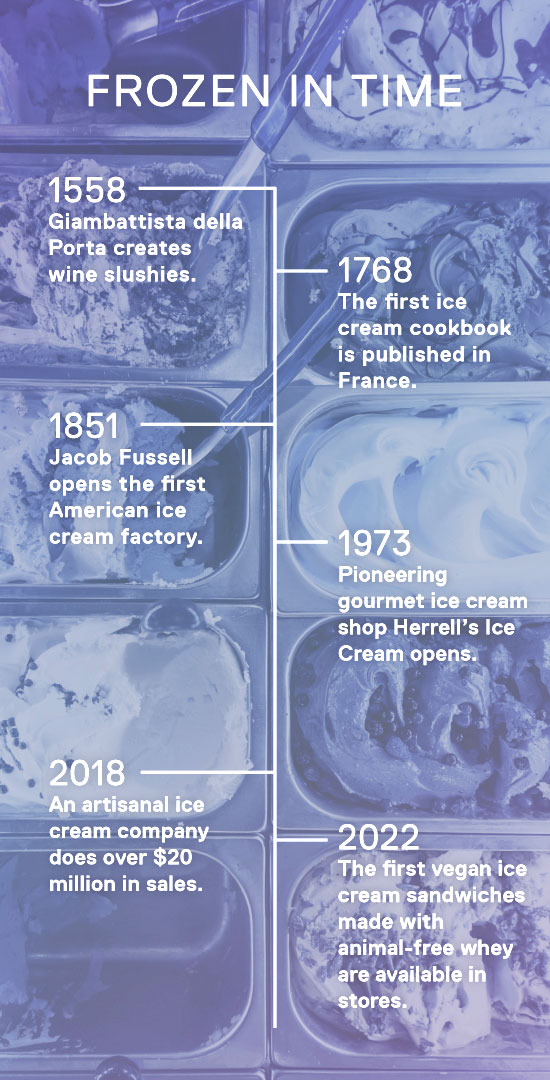

The answer to that question came in 1558 when an alchemist from Naples named Jam Batista [foreign language 00:05:58] decided to turn his attention to the science of freezing.

Jeri Quinzio:

One of his many experiments was to freeze wine in glasses. To do that, he mixed saltpeter with ice, and he immersed a container of wine diluted with a bit of water in the pot of ice and saltpeter, and managed to make some mixture that was slushy. I like to call them wine slushies. They became a big hit on banquet tables in that era.

Walter Isaacson:

Salt makes ice colder by lowering the temperature at which water freezes, almost cold enough to freeze wine. Before long the success of wine slushies had chefs wondering what other foods might be tastier once frozen.

Jeri Quinzio:

Cooks had long made custards and creams and all sorts of dairy based desserts, so it’s a small step from making a custard to adding a little bit more sugar and freezing that using the new freezing technique and you have ice cream. Finally, we had real frozen ices and ice creams.

Walter Isaacson:

In 1768 the first cookbook devoted entirely to ice cream was published in France. Its author said ice treats should have textures like snow, so their soft and spoonable, as opposed to earlier recipes, which said they should be slushy. It was the beginning of an ice cream boom in Europe. By the early 19th century, some notable American travelers started bringing recipes home to the US. While Frederick Tudor’s burgeoning ice trade was increasing ice cream’s availability, making it was still a time consuming and strenuous process.

To keep the mixture from freezing into a solid block, they had to continuously stir it. A process that became more laborious as the ice cream started to thicken. While the hard work paid off in a smooth and delicious dessert, it was exhausting. So in 1843, a woman named Nancy Johnson from Pennsylvania invented a new type of ice cream freezer. This new freezer used a crank that when turned moved a corresponding paddle that made the mixture easier to stir. This machine was used as a prototype for commercial ice cream makers. In 1851, a dairy salesman named Jacob Fussel opened the very first ice cream factory in America.

Jeri Quinzio:

He was a Quaker. He was a very ethical person. He sold his ice cream at what he believed was a fair price. Some of the local ice cream makers sold their ice cream at a much higher price, and they wanted Fussel to increase his price to align with theirs. He said, “No, no, he was selling his ice cream at a fair price.”

Walter Isaacson:

And because the growing ice trade meant that boats and railroad cars could Ship frozen products further, Fussel was able to expand his business and send ice cream across the US.

Jeri Quinzio:

So his business was the beginning of a more industrial produced ice cream. It got to the point really, when street vendors started making ice cream and selling it for a penny.

Walter Isaacson:

They were called penny licks. Penny licks were small glasses filled with ice cream that customers would lick until they were empty. Soon penny licks were replaced by a more popular vessel, the ice cream cone.

Jeri Quinzio:

The ice cream cone is another interesting story. What you often read is that at the 1904 World’s Fair, an ice cream vendor ran out of cups for his ice cream, and a waffle maker next to him saw his dilemma, rolled his waffle into a cone shape and let the ice cream vendor fill it with ice cream and the ice cream cone was born. Well, it’s a nice story, and it might be a true story we don’t really know.

Walter Isaacson:

What we do know for sure is that the first patents for ice cream cones were issued at the turn of the 20th century. But better production and serving methods weren’t the only factors that helped bolster America’s love affair with ice cream. One of the biggest booms for the industry occurred quite unexpectedly when the US outlawed alcohol in the 1920s.

Jeri Quinzio:

So prohibition, it sounds strange, but apparently when saloons closed people and often men went to a soda fountain and had an ice cream instead. There was actually a little song about, dad’s not stopping at the bar anymore, he’s stopping at the soda fountain and bringing home a pint of ice cream for the family.

Walter Isaacson:

By the end of Prohibition, national ice cream consumption had grown by more than 100 million gallons per year. By the start of World War II, ice cream was so popular in America that, as many countries banned the production of ice cream as a way to ration supplies, US officials gave it the designation of an essential food. They realize that ice cream improved morale for soldiers on the front line. The Navy was even outfitted with ice cream equipment so sailors could make their own while at sea. But as the war dragged on, ingredients became harder to find. This forced ice cream manufacturers to substitute corn syrup for sugar and corn starch for cream. Unfortunately, by the end of the war, manufacturers realized that they could continue to make this cheaper syrup sweetened ice cream without hurting sales. Profits soared, but for some the memory of something better still lingered.

Judy Herrell:

Sometimes I wonder if he really realizes how important he was to the industry.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Judy Harrell. She’s referring to Steve Harrell, her ex-husband and current business partner. Steve and Judy run Herrell’s Ice Cream in Northampton, Massachusetts. First opened in 1973, Herrell’s Ice Cream is known for pioneering the renaissance of the all natural, fresh, gourmet ice cream trade in the US. It’s the same ice cream that Steve made with his uncle when he was a kid.

Judy Herrell:

The person who really inspired Steve was going to be his great uncle Raymond, both kind of inventors, crazy mad scientists. Uncle Raymond didn’t like the work of cranking, the hand crank. So when Steve was six or seven years old he remembered Uncle Raymond creating and building a contraption that was belt driven with a motor that would crank the ice cream for him. It would always come out perfect because it was at the same speed all the time. I think that when it came down to him wanting to own his own business, he thought about the fun he had making ice cream with his family, knew he had something that was different than was out there currently and decided to do that.

Walter Isaacson:

Hand crank machines churn slower than their commercial counterparts, meaning less air is pumped into the mixture and less air in the mixture results in thicker creamier ice cream. But Steve knew that if he used a hand crank machine for his business, he’d never produced enough product to turn a profit. The problem was big commercial machines that created low air ice cream didn’t exist. So just like his Uncle Raymond, Steve decided to build one himself.

Judy Herrell:

He bought a brand new white mountain freezer, commercial version. The dasher, which is what makes the ice cream turn, and it scrapes the ice cream off the wall of the freezing element. So what Steve did is he put a gear reducer on the motor that worked the dasher, so the dasher went slower, and that was revolutionary.

Walter Isaacson:

The result was super creamy ice cream, and it was a delicious wake up call for millions of taste buds dulled by the big ice cream manufacturers whose product was full of air, additives and preservatives. But Steve wasn’t done transforming the ice cream industry just yet.

Judy Harrell:

Steve’s an innovator in general, and he also really enjoys playing with his food. So what Steve did was he thought, “Why can’t I put Heath bar inside my ice cream?” So he created a method called The Mix in, and nobody had ever conceived of doing anything like that. So if you loved Oreos, which was his second favorite love, you could put your cookies in the ice cream.

Walter Isaacson:

There was some debate about who invented cookies and cream ice cream, but Steve was undoubtedly one of the first, if not the first to make it. His cookies and cream ice cream was an immediate cult-like success.

Judy Herrell:

He opened the store with 32 gallons of ice cream. He went through the 32 gallons within a day, he closed the store, had to hire a bunch of people, bought a walk-in freezer and reopened to these incredibly long lines.

Walter Isaacson:

And as word spread of his success, Steve’s shop caught the eye of other wanna-be ice cream entrepreneurs.

Ben Cohen:

Steve’s homemade ice cream was the mecca for homemade ice cream on the east coast.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Ben Cohen, the co-founder of the world famous Ben and Jerry’s Ice Cream.

Ben Cohen:

I met Jerry in junior high school. We were in the same gym class together. We were the two slowest fattest kids in the class. We kind of met at the back of the pack, way, way at the back of the pack running around the track.

Walter Isaacson:

When Ben’s dream of becoming a potter didn’t materialize, and Jerry failed to get into med school, they decided to go into business together.

Ben Cohen:

Well, we wanted to make the kind of ice cream that we like to eat, and we wanted to make it all natural. We researched ice cream quite a bit, and we learned that the ice cream that people used to make at home on the back porch in the old days was really the best ice cream there is.

Walter Isaacson:

This old style homemade ice cream was just like the ice cream Steve was making. So Ben and Jerry reached out to Steve, who was happy to share his secrets, including how to slow down the dasher to make the perfect ice cream. They were armed with the magic rotation per minute formula and a commitment to natural delicious ingredients, but launching their company was more difficult than either Ben or Jerry expected.

Ben Cohen:

Starting a business, especially a small, underfunded business is nothing but challenges. We were sleeping in the back room on top of the freezers at night. It was our entire lives. We didn’t do anything except eat, sleep, and work at the shop.

Walter Isaacson:

But their hard work paid off. Building off the success of Steve’s Mix Ins, Ben and Jerry focused on creating their own trademark, intensely favored big and chunky, whimsical ice cream flavors. It was unlike anything the industry had seen before.

Ben Cohen:

When we first came out with Cookie Dough, we were making chocolate chip cookies in the store and we were making ice cream in the store. The guy who was making the cookies talked to the guy who was making the ice cream, and they said, “Hey, why don’t we just stick in some raw dough?” They did it, and that created phenomena in terms of the sales of that flavor. Now Cookie Dough’s pretty much a standard flavor for most any ice cream company.

Walter Isaacson:

Flagship flavors like Cherry Garcia, Chunky Monkey, an American Dream soon followed. Eventually, Ben and Jerry were able to stop sleeping on top of their freezers. Today, Ben and Jerry’s is a household name. Last year they did more than $900 million in sales, making it the most popular ice cream brand in the US. But perhaps more impressive than their sales is how they’ve changed the industry. Ben and Jerry’s helped kickstart the premium ice cream wave. They’ve introduced millions of Americans to better quality ice cream and paved the way for the artisanal ice cream makers who are now taking the industry by storm. But how exactly is artisan ice cream different from most big brand companies? Well, artisan ice cream is a small batch product that’s usually made with the most indulgent and high quality ingredients.

Ben Van Leeuwen:

When we started making and selling Van Leeuwen ice cream in 2008, there were not a lot of producers or maybe none who were making ice cream the way we make ice cream.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Ben Van Leeuwen, co-founder and CEO of Van Leeuwen Ice Cream.

Ben Van Leeuwen:

So 18% butter fat, 8% egg yolks, no funny stuff, just milk, cream, sugar, eggs, little bit of sea salt, and then these amazing flavoring ingredients.

Walter Isaacson:

The idea for artisan ice cream came to Van Leeuwen back in 2003 when he decided to leave school and go abroad. With the money he saved that summer driving an ice cream truck he spent a year traveling and more importantly, experiencing the local cuisine of cultures all across the globe.

Ben Van Leeuwen:

So I bought a one-way ticket to Italy, and I spent about eight and a half months traveling throughout Europe and Asia with a very small backpack, more like a book bag, had like one pair of pants, one pair of shorts, like two pairs of socks. As I say this, it sounds cliche, I was affected by how good the food was in Italy. Of course, the foods good in Italy and France and Spain and Thailand and Vietnam and Lao. But these were places where good food was just the default. I was really excited finding these places where good food was normal, where it was just a part of life. So those experiences really shaped me. But really the core of that was just trying good stuff and being excited by the idea of good food just being accessible and sort of normal.

Walter Isaacson:

And when Van Leeuwen returned to New York with a passion for premium food, it was the most basic treat that inspired what he did next.

Ben Van Leeuwen:

It was a warm afternoon and I saw Mr. Softee ice cream truck. In that moment the idea came to me. It was a simple idea. Let’s build an ice cream truck and let’s sell really good ice cream off of that truck.

Walter Isaacson:

Van Leeuwen recruited his brother and then girlfriend to join his venture, and Van Leeuwen Ice Cream was born.

Ben Van Leeuwen:

We started with a used 1988 Chevy P30 step van that we bought on eBay for $2,500, and we retrofitted that into the first Van Leeuwen ice cream truck.

Walter Isaacson:

The first Van Leeuwen truck was a lucky find, but sourcing the right ingredients took a bit more effort. Their first ice creams were made with Sicilian chocolate, vanilla beans aged in vodka and strawberries ripened in volcanic soil. They were hopeful that their uber premium artisanal ice cream would be just what New Yorkers were craving.

Ben Van Leeuwen:

We had the ice cream truck and we were ready to go. We were nervous, right? We had just spent $60,000 that we raised building this truck and making some ice cream, and we were finally ready to start generating some revenue.

Walter Isaacson:

It was a warm and sunny day in June when the Van Leeuwen truck were old onto Wall Street. Parking was hard to find, so they decided to try Canal Street, but by 2:00 PM they still had not sold a single cone.

Ben Van Leeuwen:

So this was bad, at this point we’re freaking out. We’re like, “Okay, this was a stupid idea. The people who said it was a stupid idea were right.” So we were like, “All right, let’s try one more location, I guess, before completely giving up.”

Walter Isaacson:

So they threw up a Hail Mary and drove their truck out to Soho in a last ditch effort to try and make a sale.

Ben Van Leeuwen:

So we parked on a side street, we start getting set up, and before we’ve even opened the window a line starts forming. By the time we open the window, there’s 25 people waiting in line. We started scooping ice cream. We started serving customers. People were so interested in who we were as a brand, what we were doing, what we were serving. We said, “Wow, this works.”

Walter Isaacson:

By the end of the first year, Van Leeuwen Ice Cream sold more than $400,000 of product. The following year, they hit the $1 million mark, and in 2018, they did over $20 million in sales. Van Leeuwen’s success inspired lots of other uber premium ice cream makers to enter the market. In fact, when grouped together, these small batch artisanal brands sell more product than Ben and Jerry’s, making it the best selling ice cream in America. But while ice cream quality continues to rise, there’s one group of consumers who have felt left out in the lurch, vegans. Whether for ethical or dietary reasons, more and more people are going dairy free. While some progress has been made with cocoa butter and nut and oat milks, there’s no denying that when you take the dairy out of ice cream, it still tends to taste, well vegan.

Ryan Pandya:

It is the delight of the mix ins and inclusions in a Ben and Jerry’s pint that inspired us to make some of the delicious flavors in Brave Robot.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Ryan Pandya. He’s the co-founder and CEO of Perfect Day, the biotech company behind Brave Robot Ice Cream. Ben and Jerry’s is a source of inspiration for Pandya, but Perfect Day is transforming ice cream in a way that earlier industry pioneers likely never thought possible. In fact, Perfect Day is not only revolutionizing ice cream, but the entire dairy industry. The milk protein they use is essentially identical to the milk protein found in traditional dairy products, except for one big difference, it doesn’t come from an animal. It’s grown in a lab. Pandya started his business because, much like his business partner, he was a vegan who loved dairy.

Ryan Pandya:

We were both 22, 23 years old. Indian American bioengineers. Went vegan and hated it, right? On top of all of that, we had the idea to use precision fermentation to make the exact same proteins found in milk in hopes of being able to create a much more scalable dairy supply chain that could be sustainable, that could be kinder, greener, and futureproof.

Walter Isaacson:

Precision fermentation is a process where scientists inject milk protein DNA into an organism called micro flora. Micro flora create their own proteins during fermentation, but when they’re injected with milk protein DNA, they reprogram themselves to create milk proteins instead.

Ryan Pandya:

Essentially what we did is we Googled, “What is the DNA sequence of milk protein,” then we got it. Then we copied it and pasted it into an email to one of those companies that just creates DNA molecules out of thin air. They mailed it to us like a week later, and it was like a couple hundred bucks. It is that simple, but what is not easy is making it efficient, scalable, low cost, guaranteed to be safe in all the ways that the regulatory environment and our commitment to ourselves, our employees, our families, our world, all those other pieces take a lot of work.

Walter Isaacson:

Another challenge for Pandya was convincing consumers his ice cream was as good as traditional dairy options. He knew consumers would be skeptical of real dairy ice cream made without cows. So he went into the field to test this product.

Ryan Pandya:

We had this ice cream truck, we wanted as many people as possible to try our product and give us feedback, and we wanted to have these authentic conversations with ice cream lovers and people walking by. It was the weirdest thing because someone would walk by and were like, “Hey, do you want a free sample of ice cream? It’s lactose free, it’s cholesterol free, it’s vegan, but you’d never know.” They try it and they’re like, “I don’t get it, you just handed me free ice cream.” They didn’t even realize that anything was different about it.

Walter Isaacson:

Brave Robot Ice Cream has been a gift to the vegan community now available in more than 5,000 stores across the US. It matches the ever elusive mouth feel and taste of milk-based ice cream. But even more important than taste are the substantial environmental benefits Perfect Day’s lab grown milk proteins provide. In fact, animal free dairy products like Brave Robot ice cream have the potential to reduce dairy industry greenhouse emissions by 97%.

Ryan Pandya:

You can imagine as companies start to replace their dairy supply chains with the animal free version, that again, has really no difference in terms of functionality, versatility, nutrition. It’s just made in a better way that impact can really be achieved.

Walter Isaacson:

Perfect Day is creating ice cream and other dairy products that reduce our environmental impact without sacrificing the delicious taste we’ve come to love, and it’s our love of this cool, sweet, creamy tree that’s helped spawn disruption across the industry for centuries. Whether it’s a trip across the tropics with a boatload of ice, or a Jerry rigged ice cream maker, a mix in recipe of cookies and candy, or lab grown milk protein. We’re grateful for every last spoonful of innovation because you scream, we scream, we all scream for ice cream. I’m Walter Isaacson, and you’ve been listening to Trailblazers and original podcast from Dell Technologies who believe there’s an innovator in all of us. If you’d like to learn more about the guests on today’s episode, please visit delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

Ben Cohen

is the co-founder of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream. In 1978, he and his childhood friend, Jerry Greenfield, opened a homemade ice cream parlor in an old gas station in Burlington, Vermont, on an initial investment of $8000. Ben & Jerry’s ice cream pioneered many unusual flavors and an equally unusual business philosophy that sought to integrate social concerns into their day to day business activities.

Ben Cohen

is the co-founder of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream. In 1978, he and his childhood friend, Jerry Greenfield, opened a homemade ice cream parlor in an old gas station in Burlington, Vermont, on an initial investment of $8000. Ben & Jerry’s ice cream pioneered many unusual flavors and an equally unusual business philosophy that sought to integrate social concerns into their day to day business activities.

Ben Van Leeuwen

is the CEO and co-founder of Van Leeuwen Ice Cream. Van Leeuwen Ice Cream was started in a yellow truck on the streets of NYC in 2008 and helped pioneer the modern artisanal renaissance in the ice cream industry.

Ben Van Leeuwen

is the CEO and co-founder of Van Leeuwen Ice Cream. Van Leeuwen Ice Cream was started in a yellow truck on the streets of NYC in 2008 and helped pioneer the modern artisanal renaissance in the ice cream industry.

Jeri Quinzio

is a writer specializing in food history. Her book, Of Sugar and Snow: A History of Ice Cream Making, won the 2010 International Association of Culinary Professionals award in food history. Her other books include Pudding: A Global History, Food on the Rails: The Golden Era of Railroad Dining and, most recently, Dessert: A Tale of Happy Endings.

Jeri Quinzio

is a writer specializing in food history. Her book, Of Sugar and Snow: A History of Ice Cream Making, won the 2010 International Association of Culinary Professionals award in food history. Her other books include Pudding: A Global History, Food on the Rails: The Golden Era of Railroad Dining and, most recently, Dessert: A Tale of Happy Endings.

Ryan Pandya

is the co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of Perfect Day, a consumer biology company on a mission to create a kinder, greener tomorrow by developing new ways to make the foods you love today — starting in the dairy aisle. Their Brave Robot ice cream uses lab-grown dairy protein to create real dairy, vegan ice cream.

Ryan Pandya

is the co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of Perfect Day, a consumer biology company on a mission to create a kinder, greener tomorrow by developing new ways to make the foods you love today — starting in the dairy aisle. Their Brave Robot ice cream uses lab-grown dairy protein to create real dairy, vegan ice cream.

Judy and Steve Herrell

own and run Herrell’s Ice Cream in Northampton Massachusetts. Judy co-owned Herrell’s Ice Cream in Northampton Massachusetts since the early 1980’s with Steve Herrell of ice cream fame. Steve Herrell was the innovator of the ice cream mix-ins customizing ice cream by adding popular candies and cookies to his artisan ice cream. He invented flavors like Cookies & Cream and Heath Bar Crunch.

Judy and Steve Herrell

own and run Herrell’s Ice Cream in Northampton Massachusetts. Judy co-owned Herrell’s Ice Cream in Northampton Massachusetts since the early 1980’s with Steve Herrell of ice cream fame. Steve Herrell was the innovator of the ice cream mix-ins customizing ice cream by adding popular candies and cookies to his artisan ice cream. He invented flavors like Cookies & Cream and Heath Bar Crunch.