PowerStore: Effective Techniques for Assessing Storage Array Performance

Summary: How to assess performance of a storage array using proper approaches and techniques for measuring and analyzing performance of an array.

Symptoms

The user is testing or benchmarking or validating a new array prior to going live and does not believe the performance being achieved is acceptable.

A common tendency is to look for simple testing approaches to validate new storage. While using simple tests can provide a positive or negative result, it often portrays an uncharacteristic view of storage performance, as it does not reflect a real production workload.

Some of the simple tests that may be irrelevant and distracting from the wanted workload are:

- Performing single-threaded write tests

- A file-copy of one or more files

- See here

for Microsoft's explanation regarding file-copy testing.

- See here

- Testing performance by dragging and dropping files (Copy and Paste)

- Extracting/deleting/creating files/folders

- Using testing methods that are not considered reflective of the workload/environment

- Using synchronous instead of asynchronous load engines/workloads

Cause

When testing network I/O performance for a storage array or file server, ensure that the tests reflect real I/O patterns of the data processing environment. Simple tests, like single-threaded read or write tasks, may be tempting but they do not provide valid acceptance testing. These tests do not compare to the activities of multiple users and applications accessing shared storage.

If the storage system is needed for sequential, single read/write functions, then single-threaded testing is appropriate for acceptance testing. However, if the system must support multiple users and applications with concurrent read/write activities, the testing should reflect the real business workload.

Resolution

- Test using variables that resemble what the real workload/environment is going to be. Remember that most tools are simulators and never achieve 100% of a true production workload simulated.

- If the workload ranges widely, consider doing multiple iterations of Read/Write tests with varying block-sizes and access patterns.

- Use multithreaded and asynchronous operations or tests to ensure parallel or concurrent performance capabilities and ensure that overall aggregate throughput potential is being exercised.

- Consider and review industry standard benchmarks for the equipment being assessed as they relate to your business's production workload.

- Avoid testing against empty or low space-usage file system and or Volumes. If you do not preallocate space on Write workloads, you can see latency due to on-the-fly-allocation of space during the test.

- Do not forget to test Read I/O as this is usually the dominant of the two in most environments. Be mindful of packet/frame-loss in the network infrastructure during the testing.

- Verify that you are testing against multiple devices in order to simulate a typical environment with many hosts or clients. For example, on PowerStore, a good number is 16 Volumes. Volume count typically matches the numbers of hosts or clients used (physical or virtual); this is where concurrency is achieved.

Benchmarking Tools and Simulators

Keep in mind that most tools are simulators and likely never get 100% of a true production workload simulated. These benchmarking tools are used to get an idea about how performance could, should, or would be in certain situations. Dell does not own these tools and is not responsible for any issues or problems that may be associated with them.

With any performance testing situation, ensure that tools with asynchronous and multithreading capabilities are used. Examples of these tools are:

- Flexible I/O Tester (FIO)

- IOmeter

- Vdbench

(requires an Oracle account)

- NFSometer

(Fedora/NFS only)

- Intel's NAS Performance Checklist

Avoid the following types of tests:

- Copy and Paste

- Drag and Drop

- Single file system backup to disk

- DD Tests

- Rlarge

- Wlarge

- Mkfile

- Unzipping, Extracting, and Compressing

Additional Information

A low IOdepth (or not high enough) can limit your potential throughput depending on the situation. Therefore, always verify that IOdepth is high enough to reflect or emulate the concurrency requirements of a workload. An IOdepth that is too low might not correctly use the device to its full potential. Also, be wary of too high of an IOdepth, this can cause some significant queuing on the device and depending on the service time of the device, there could be larger response times as a result. This can be reflective of what an overloaded system could look like.

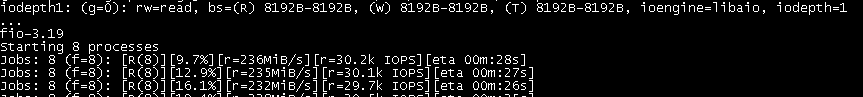

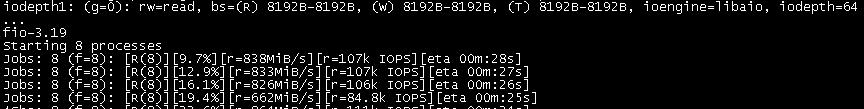

For this test, the numbers are significantly lower when there is an IOdepth of one compare with an IOdepth of something more real-world, like 64. Keep in mind that this is with an all-flash-array and thus this concept is seen in its extreme but increasingly more common, form.

"IOdepth=1" it is around ~30,000 Input and Output Operations Per Second (IOPS) avg. for the test.

"IOdepth=64" is around ~107,000 IOPS avg. for the test.

As mentioned, performance levels out at a certain IOdepth in most configurations. Here there is a queue depth of 512 and there is only a small increase in IOPS from an IOdepth of 64.

"IOdepth=512" it is around ~146,000 IOPS avg. for the test.

Async vs Sync

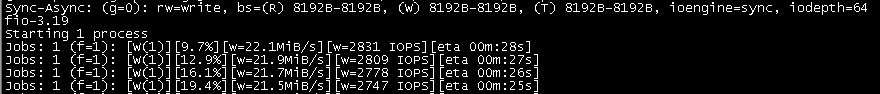

There are two major distinct engines that are used. The most popular and by far the most efficient in terms of performance are "asynchronous I/O." The less efficient and less performing type of engine is Synchronous I/O and is normally used with applications that have strict data integrity and assurance requirements. Synchronous I/O can also be found in near-zero Recovery Point Objective (RPO) replication technologies. In performance testing and benchmarking, from a host perspective, Asynchronous means that an acknowledgment is not needed for a single I/O in order to request the next I/O. In Synchronous workloads, an acknowledgment is needed for an I/O before the next is issued, and an Acknowledge (ACK) for every subsequent I/O requested. Therefore, synchronous I/O usually has a queue of 1 or less and never fully uses the resource to its full potential. Coupling synchronous operations with a low or single thread-count can severely limit performance potential, so always verify that you are doing asynchronous testing, and if you are using synchronous testing be sure to employ multiple threads unless the application environment explicitly points out not to.

Async (Libaio - Linux native async) = 1 thread

Sync (synchronous I/O):

Thread count

Threads are important. Testing should always be done using multiple threads, especially in synchronous tests/workloads. This is to attempt to simulate multiple iterations of a job/test based off of the behavior of an enterprise application's process. Multiple threads coupled with concurrent activity are where aggregate throughput of a system is achieved. Most asynchronous engines employ multiple threads, so you do not have to worry about thread count as much. Without having enough threads during synchronous workloads, you can severely limit the total potential throughput of a load test against a system.

"Multithreaded" means multiple threads doing work in parallel. For example, if you have a single device that can service 1000 IOPS in a synchronous workload, this comes out to the device having 1 ms response time without a queue (so without a queue, service time, and response time should be synonymous). Obviously, devices with 1 ms response times can do a lot more work than 1000 IOPS, and this is achieved by stacking multiple threads or parallel streams of the same workload. So, if you increase the threads (or "things doing this specific job") to 10, now you have 10 individual threads doing I/O to a device at 1 ms. Each individual workload thread is still getting 1 ms which means each thread is still only achieving 1000 IOPS, but now the whole "process" or "job" that is being run by these multiple threads is getting 10,000 IOPS.

There are tools and workloads that can adequately hit a device's limits with a single thread, and some need more. In summary, when simulating a synchronous load, you want to have as many threads/workers/streams as possible without affecting the overall response time. There is a point where increasing the thread count stops having a positive effect (when the device gets 100% busy). Generally, with Asynchronous workloads, thread count is taken care of by default. For example, below you can still see a difference between 1 thread and 10 for an asynchronous workload, albeit not significant. Moral of the story is that with asynchronous workloads, you should not have to worry about threads as much.

A single thread here can achieve 68,000 IOPS using "libaio" (async) engine.

If you increase the threads (numjobs) to 10, you can still see an increase up in the IOPS.

When it comes to synchronous workloads, while this is an extreme case, you could have two major factors that make this a bad performing test, being the synchronous nature.

send I/O-1, wait for ACK, send I/O-2, wait for ACK so onAnd not being able to stack multiple threads for the same purpose.

job1=send I/O-1 - job2=send I/O-1 - job3=send I/O-1.....job1=get ack, send I/O-2 - job2=get ack, send I/O-2 - job3= get ack, send I/O-2 so on

Direct flag

Bandwidth (MB/s) vs. Throughput (IOPS)

Bandwidth (MB/s) - Bandwidth is the measure of data that you can fit at once (or within X interval usually "per second") on a pipe or system. This means that it is measuring how much data you have transferred over a period of time. Although bandwidth and IOPS are not mutually exclusive, you can have higher or lower bandwidth numbers with the same amount of IOPS, it all depends on the block size. Remember, you are not measuring speed with bandwidth, the speed is something entirely different and while it does affect bandwidth, it is usually something you cannot control with heavy-bandwidth workloads. Therefore, if testing for bandwidth, always use larger blocks (within reason) so that your data per I/O is larger than if you would be testing for IOPS, since larger blocks will naturally take longer to service. If, for example you want to achieve 1 MB/s but you are using 8 KB block sizes, you must push around 125 IOPS to achieve this. However, if you were using 512 KB blocks, then it would take only two (2) IOPS.

(If you were to keep the 125 IOPS and still increase the block-size from 8 KB to 512 KB, you are now pushing 64 MB/s!)

However, because there is more data within a single I/O, it usually takes longer to "package" that I/O (finding, stringing together and so on). Therefore, service times can naturally be higher. Sometimes you have a smaller queue, so your response times although naturally higher, should be rather close. Keep in mind that while response time does play a role in how much bandwidth you can achieve, the increase in how much data there is per I/O usually outweighs any slight increase in Response Time (RT) per that type of I/O. Since response times are higher, you do not want large-block workloads to have to be random. So, bandwidth workloads tend to be sequential. When you introduce a random nature to a large block workload, your steady data transfer rate is consistently interrupted, and you start to feel the effects of the slightly higher response times per I/O.

Throughput (IOPS) - Throughput/IOPS is the most common perspective with small-block workloads, especially as they become more random. Anything over 32 KB-64 KB can be considered a large block. With throughput, the above-mentioned factors are most important (things like thread count, sync, or async, queue depth and so on). Here you are trying to measure not how much overall data you can transfer during X interval, but rather how many individual packages (I/O requests) carrying that data you are trying to service (every x interval). Environments like OLTP (banking) care little about how much data they can transfer because their data footprint is usually small. However, these small data-sets can be, and are normally busy. These data-sets have a high skew (a small amount of space is referenced but vary aggressively and consistently). The small packages of data usually only contain requests to alter/update blocks with numerical or smaller string values, and therefore large I/O packages are not required. However, because of the nature of transactions and because there are so many of them, we want to verify that we can keep up with each individual demand. Usually, the smaller the block-size the more IOPS you can achieve in a given scenario, and although small block workloads are mostly associated with random access, you can achieve even more throughput with small block sequential workloads. However, small block sequential workloads are specific and not as common, so test these scenarios only if your environment calls for it.