By Susan Kuchinskas, contributor

Lafora disease is an inherited, severe form of epilepsy that strikes during adolescence and is often fatal within 10 years of onset. With fewer than 5,000 people in the U.S. affected, it’s an orphan disease that hasn’t been a prime target for research.

Chelsea’s Hope plans to change that. The nonprofit was started by the families of people with Lafora to raise funds to develop treatments and find a cure. Says research director Kit Donohue, “Having a direct connection between scientists and the community helps ensure the science is being as efficient as possible and addressing the direct needs of the patient community.”

But Chelsea’s Hope found that, because of the way research is funded, promising findings weren’t always followed up on.

“We had multiple therapies in the pipeline, but hit some real speed bumps in getting them into clinical trial. We had relationships with pharmaceutical companies, but when the economy tanks, rare diseases are always going to be on the cutting block,” Donohue said.

That’s why Chelsea’s Hope partnered with Vibe Bio. Vibe creates DAOs for patient groups. DAO stands for decentralized, autonomous organization, and it’s a way of bringing together diverse groups of people with a common goal. Vibe’s DAO for Chelsea’s Hope acts as a hub for info and communication.

Having a direct connection between scientists and the community helps ensure the science is being as efficient as possible and addressing the direct needs of the patient community.

—Kit Donohue, research director, Chelsea’s Hope

DAOs are part of a new movement within science that promotes open access to information and materials, as well as funding. Sometimes called decentralized science or open science, the idea is to build stairs to the ivory tower that anyone can climb.

“Vibe is trying to provide patients with an unprecedented level of ownership in the drug development process,” says Vibe CEO Alok Tayi. “We’re at an inflection point in drug development. There’s a proliferation of high-potential modalities and many more approaches we can take to treat disease. Now, the challenge is not finding cures, but funding them.”

Each of Vibe’s DAOs serves as an online coordination hub to connect patient communities directly to investors, scientists and other experts. The DAOs have no central authority; all members help decide what treatments to study and which projects should be funded. Once a project is chosen, actual drug development is performed by experienced drug developers, scientists, contracted research and manufacturing organizations, and medical establishments for clinical trials.

Funding life-changing research

Vibe’s DAOs plan to raise money through the sale of cryptocurrency tokens to investors. If treatments are commercialized or licensed by pharmaceutical companies, this capital returns to the DAO and the patient advocacy organization, so it can be used to fund future projects.

The cryptocurrency tokens let investors help govern the actions of the DAO, but they won’t provide investors with an economic interest in any treatments or intellectual property.

In addition to Chelsea’s Hope, Vibe Bio has partnered with NF2 Biosolutions, a patient advocacy organization, to launch Merlin Therapeutics and find gene therapies for Neurofibromatosis Type 2, also an orphan disease.

Molecule is another funding platform organized around DAOs. While a lot of research money gets funneled to big incumbents, Molecule helps researchers raise funds from patient groups, researchers, charities, venture capitalists and pharmaceutical companies. It aims to let anyone build their own biotech DAO.

“What WordPress did for websites, we want to do for DAOs. We want to create new organizational structures that have a low barrier to entry, are intrinsically collaborative and can coordinate capital and [contributions] from any participant,” says Heinrich Tessendorf, Molecule’s marketing manager.

The difference between crowdfunding and Molecule, he explains, is that every member of a DAO has a proportional say in how the thing should work, thanks to blockchain tokens weighed according to the level of investment.

A team of experts evaluates proposals coming onto the platform and then may propose them to DAO members.

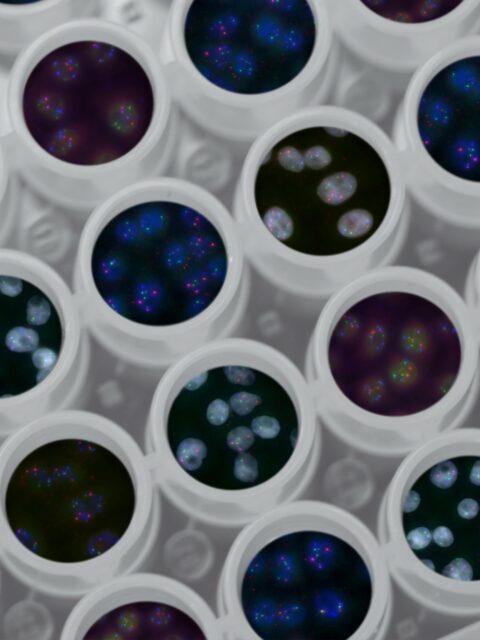

Its first DAO, VitaDAO, supports longevity research. VitaDAO has screened around 100 projects and invested some $2.5 million in seven of them. It recently awarded $252,000 for research into reducing age-related disease by clearing senescent cells from the body. Another lab received $300,000 to look into how dysfunctional mitochondria affect healthy aging. Molecule plans to launch other DAOs targeted to other aspects of health or disease.

Decentralization is key to Molecule’s approach. Its participants come from all over the world and can, like the open-source software development paradigm, contribute as little or as much as they want.

What’s the payoff for Molecule participants? Contributors get NFT tokens representing intellectual property. The tokens give them governance rights. Theoretically, they could sell the tokens; however, it’s not clear there’s any market for them.

Freely shared resources

Science costs money. Obtaining the chemicals for experiments can be a significant barrier to researchers not located in wealthy countries. Some labs ship molecules or the tools to make them, free of charge, to anyone who asks.

The FreeGenes Project, out of Stanford University with support from the BioBricks Foundation, is a free collection of enzymes for DNA design. The project was started by Jenny Molloy of the University of Cambridge Open Bioeconomy Lab and is now run by Stanford associate professor of bioengineering Drew Endy.

FreeGenes has shipped some 1,500 orders—and its users show the power of decentralized science. Endy says around one-third of orders are from academics who can’t afford to buy them from suppliers. Another third is from what he calls “’bio-curious’ people who are immigrating in” to bioscience. Such open-source tools and access to enzymes and other chemicals let people without formal bioscience training take part in research.

And the third user group is very small companies in local bio-economies.

“There’s a whole B2B economy underlying biotech that’s amazingly powerful and professional. These local companies can do useful things within the biotech sector—and I didn’t know these companies existed. It reminds me that all biology is local,” Endy says.

While it may seem alarming that anyone can access these free genes—and wittingly or unwittingly create a bioweapon—Endy says FreeGenes requires people to use their real names and addresses, checks all orders against government screening lists, and doesn’t supply infectious agents or materials that could cause harm.

“Could someone use a general-purpose E. coli expression vector to express a toxin?” Endy asks. “Yes, presuming they could find or source the gene expressing the toxin from someone else. For comparison, could someone go to a hardware store and buy a hammer and hit someone? Yes. We are being as responsible as a hardware store.” He adds, “If people can’t learn, they can’t do. Open science is a precondition for democratizing science or ‘sciencing’ democracy, which are two sides of the same coin.”

The Phage Directory is another example of freely shared biological materials. Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that selectively kill bacteria. They’re used to fight drug-resistant infections. But there are thousands of phages, and it can be hard for clinicians to find one that works.

If people can’t learn, they can’t do. Open science is a precondition for democratizing science.

—Drew Endy, associate professor, Stanford University

The Phage Directory brings together a decentralized group of scientists who have phages available. The directory includes 440 researchers and 100 more organizations, all standing by to answer urgent requests for that one phage that might mean a cure for a single patient.

Free to publish and read

Publication of scientific papers is essential to scientists’ careers and the prestige of their institutions. But the major scientific journals are difficult to break into, and they’re accused of cronyism and prejudice. Meanwhile, subscriptions to journals or the fee to read a single article online are barriers.

The Public Library of Science (PLOS) was founded in 2003 on an open-access model: Papers are immediately available to read, free of charge, under Creative Commons licenses. There are now more than 18,000 open-access journals.

It’s important to note that open access doesn’t mean anyone can publish. Most journals use the same peer-review process as traditional journals.

Open access is a boon for researchers and students, but someone has to pay to keep the lights on. PLOS and many other open-access pubs charge article processing fees to authors or their institutions. (PLOS waives fees to those who can’t afford them.)

Instead of charging authors or institutions, the Quartz OA project aims to provide financial support for open-access publishers and authors with a browser extension that automatically collects a micro-payment when someone reads an article, supporting authors, editors and reviewers. More funds will come from libraries, institutions and voluntary individual membership fees.

Decentralized science and open access—whether to publications, tools or researchers themselves—can ignite and streamline research, Donohue of Chelsea’s Hope believes. She says, “What drives scientists is to make the world a better place. When they build relationships with patients and family members, we’ve seen a new spirit of collaboration. When they can see and experience firsthand what’s happening in patients’ lives, that puts a face on the science.”

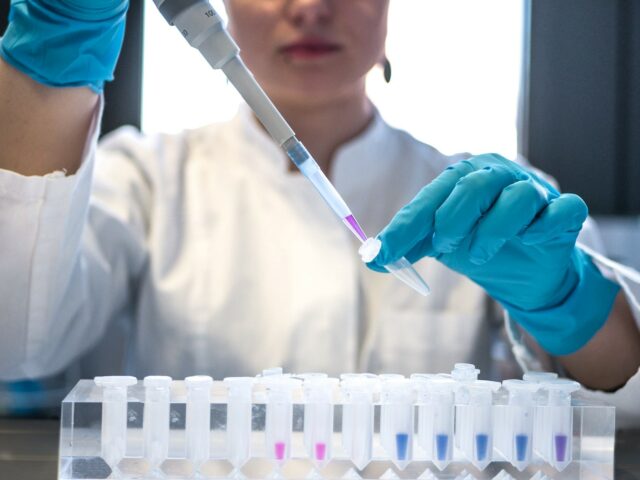

Lead image of a scientist pipetting colored chemicals courtesy of Julia Koblitz/Unsplash.