Walter Isaacson:

It’s a sweltering hot day in June, 2012 when a group of archeologists are rewarded with a once in a lifetime discovery. Lying deep within the center of a sand dune, they’ve unearthed the head of a massive beautifully carved Sphinx, that to their great surprise is almost completely intact. But what makes this discovery even more perplexing, is where the artifact is found. These archeologists aren’t excavating deep within the Sahara, miraculously uncovering relics from an Ancient Egyptian epoch. They’re digging in the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes, in Central California. The artifact exhumed from the desert that day was one of fifteen’s Sphinx heads built to depict the Pharaoh city for Cecil B DeMille’s 1923 hit film The 10 Commandments.

When filming wrapped, DeMille did not have the budget to disassemble and properly dispose of his set, so he decided to bury it instead. And there, a few feet beneath a California sand dune, the entombed Pharaoh city sat for almost 90 years. Known for his epic sets and stunning effects, DeMille was a visionary in the field of visual effects. And his most startling effect from this biblical blockbuster was quite literally godlike. The parting of the Red Sea.

DeMille created this iconic moment by pouring the water into a small trench, then reversing the film, which successfully created the effect of parting the Red Sea. But once the sea was parted, he had to ensure it stayed parted, so he turned to one of America’s favorite desserts. Enormous slabs of jello were used to create the walls of the parted sea that Moses and the enslaved Egyptians had to pass, as they ran across the ocean floor to freedom. To make these elements appear as if they were shot together, DeMille used a technique from photography called double exposure. After shooting the walls of Jello, the film was manually rewound. Then the scene was shot over top of some of that film. When played back, everything appeared as if it was shot at the same time, like magic. Moses and his followers were running through a parted sea.

30 years later, DeMille parted the Red Sea again. This time in his 1956 version of the same film, starring Charlton Heston. Now with color and sound in his toolkit, DeMille added even more exposures to the famous shot. The extra elements resulted in a vivid realism still considered one of the greatest pre-CGI effects in film history. Without DeMille’s epic gelatin molds, and ingenious double exposures, we likely would not have the thrilling seamless visual effects we enjoy today. And much like DeMille, today’s filmmakers and visual effects artists approach their work with the same level of ingenuity, and sense of limitless possibility. I’m Walter Isaacson, and you’re listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies.

Speaker 3:

Behind the glamour of Hollywood, lies an industry turning the wheels which bring these marvels to you.

Speaker 4:

I’m going out with my new movie camera, want to come Along?

Speaker 5:

What really counts is how that equipment is used.

Speaker 6:

It’s the magic of the silver screen.

Speaker 5:

And on that, we dissolve.

Walter Isaacson:

Visual effects help filmmakers tell stories they otherwise might not be able to tell. They convince their audiences to suspend disbelief, and become fully immersed in a story. It’s a slight of hand, much like that of a stage magician, that has been refined for more than a hundred years.

Craig Barron:

It’s very hard to say when the first special effect happened, but it certainly is as old as film itself.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Craig Barron, visual effects historian and creative director at the visual effects company Magnopus.

Craig Barron:

And one of the earliest examples is from the execution of Mary Queen of Scots, I think it was in 1895. And basically the way they did it, is that the executioner raises his ax, and just before he’s about to chop off the head of the actress, they stopped the camera and they put in a dummy, continue the filming and then have the ax come down and chop off the head. For audiences in 1895, it must have been pretty horrific. Because it is horrific. It’s like, wow, you just see somebody’s head get chopped off.

Walter Isaacson:

It was a technique that became known as a jump cut. Invented by George Méliès, this effect amazed audiences and inspired early filmmakers to push the boundaries of what was possible.

Craig Barron:

Really visual effects got going under George Méliès, a French magician that was in Paris, and he wanted to use film as an extension of his magic act.

Walter Isaacson:

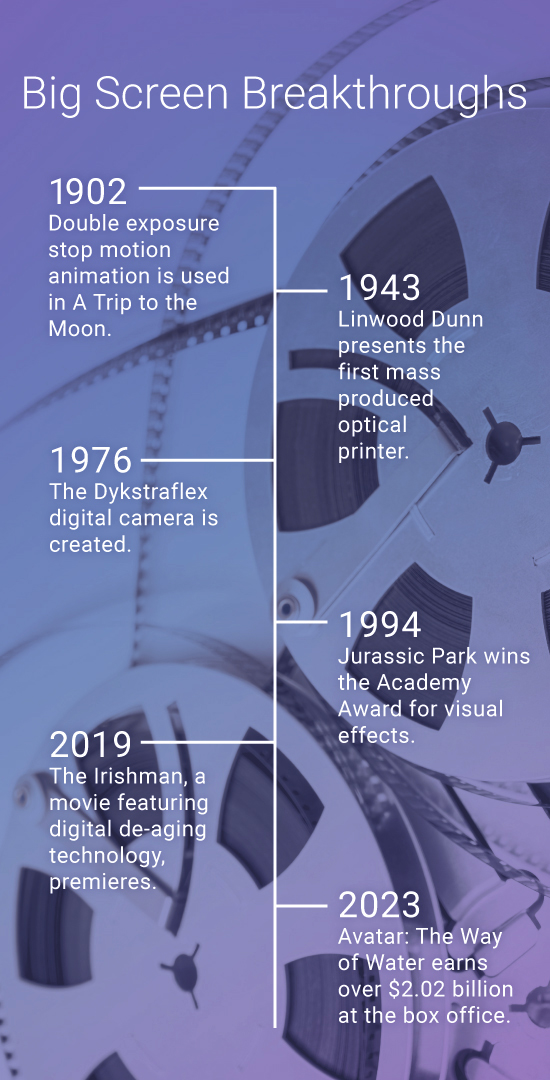

Méliès’s 1902 film, A Trip to the Moon, is considered by some to be the first science fiction movie and one of the earliest films to incorporate visual effects. It best remembered for the iconic image of a rocket ship flying directly into the eye of the moon. It was an astounding effect for the day. Created using double exposures and stop-motion animation, the techniques used and trip to the moon were later used to make a blockbuster that changed the visual effects industry forever: King Kong.

Craig Barron:

Willis O’Brien was a master in stop-motion animation, and made King Kong in the 1930s. The puppet was maybe 18 inches tall, made to look 20, 30 feet, towering above New York on that classic image of the Empire State Building that we all remember as part of popular culture.

Walter Isaacson:

Before King Kong, filmmaking was in an era of in-camera effects. Meaning effects like stop-motion and double exposures, were complete the moment they were filmed. But the visual effects artists making King Kong ushered in a whole new era, by taking effects out of the camera. They did it with a tool destined to become one of the most important innovations in visual effects history: The optical printer.

Craig Barron:

Who developed the optical printer is hard to say. Because again, it’s one of those devices that was around and ended up being adopted to visual effects work. It was originally created to copy film so they can make a copy of a movie for distribution. And then they realized, oh, if we’re copying film, we could also copy part of the film at different times and combine different scenes together using it.

Walter Isaacson:

Special effects crews could now film the set, the stop-motion animation and the live action footage separately. And then put them all together in a single shot using the optical printer, rather than using the same piece of film by repeatedly rewinding it. Suddenly, filmmakers had the freedom to finesse how they could put together images, expanding the horizons of what they could do. By the 1940s, the painted backgrounds necessary for in-camera effects made way for blue and green screens, as filmmakers learned how to insert background locations during post-production. Driven by more ambitious and visually stunning movies, film entered its golden age, cementing the importance of visual effects.

Then in 1977, a filmmaker by the name of George Lucas decided to make an epic film set in a galaxy far, far away, which likely did more to transform filmmaking and visual effects than any other movie in history. Inspired by footage of agile World War II fighter pilots, who had to evade enemies in close range aerial combat known as dog fights, Lucas decided to call his film Star Wars.

John Dykstra:

And it was dog fights in space. It couldn’t have been better for me. I was a pilot, I did aerobatics, I loved all of that stuff. So the idea of a dog fight, that was a slam dunk.

Walter Isaacson:

This is John Dykstra. He’s the artist that George Lucas hired to create the visual effects for the original Star Wars. Dykstra realized that to duplicate the frenetic speed of fighter planes, he would need to find a way to move the camera around the spaceship miniatures, instead of filming the movement of the miniatures themselves.

John Dykstra:

And the idea of being able to move the camera and follow the action, was another pursuit that I had done many times, trying to figure out how to get this camera down into this canyon in a way that would give you a sense of being very close to the surface and traveling really fast. That illusion is based on proximity.

Walter Isaacson:

Dykstra’s idea had a precedent in another famous sci-fi film. Motion cameras, or cameras that moved around a model, had been used in Stanley Kubrick’s groundbreaking 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

John Dykstra:

So you could make these great moves, and 2001 had a lot of them, where the ship would go by in a smooth continuous motion, but you didn’t really see many shots where the ship accelerated or decelerated, or where the camera panned. And if they did, they were all linear moves.

Walter Isaacson:

The images created in 2001 using motion cameras were stunning, but they were not the speedy dog fights that Lucas had in mind. For this, Dykstra would need his cameras to accelerate and decelerate, spinning and swerving around the models, movements motion cameras were not yet able to perform. He then needed the cameras to be able to repeat each pass precisely as he filmed the models, the explosions, and the backgrounds, which were then stitched together. It was an impossible level of precision to achieve without computers, which in the early 1970s weren’t available. But Dykstra knew that the Berkeley Institute of Urban Development had built something that might do the trick. They were using cameras digitally controlled by early refrigerator sized pre-computer processors, which were dropped into small city models to record routs along its miniature streets. Using this technology, Dykstra built a camera. He dubbed the John Dykstra Flex, which was used to film the legendary high speed battle scenes between the Rebels and the Empire.

John Dykstra:

It was a realization of a dream. Somebody was willing to give us the funding necessary to bring our concepts, which were not proven, together. And moreover, to assemble them into this cockamamie machine that I figured was going to make all these images and it have it work. An incredible amount of fortune. And if any one of the hypotheses had failed, it could have spelled disaster for the whole thing.

Walter Isaacson:

The influence that Dykstra and Star Wars had on the visual effects industry cannot be overstated. They introduced computers and filmmaking and by doing so, ushered in a new era of cinema, one that would eventually become dominated by digital effects.

Dennis Muren:

CGI stands for Computer Graphic Images, and it’s a term that refers to making an image. It could be a pie chart, it could be a graph, it could be a dinosaur, it could be a spaceship.

Walter Isaacson:

This is Dennis Muren. He’s the most decorated visual effects artist of all time, with a record of nine Academy Awards to his name. In 1976, Muren was hired as the second cameraman on Star Wars. During the making of the film, George Lucas founded Industrial Light and Magic, also known as ILM, a groundbreaking visual effects film company. His goal was to explore the possibilities of computers in filmmaking.

Dennis Muren:

The thing that George was looking for when he started the computer graphic division in like 1979 or 1980, was he wanted to make these movies, but they were too expensive, and they took too much hardware and too many people. And he saw that it looked like at some point, this is going to be able to be done on computers. So he took a lot of the money that he had made from Star Wars and Empire Strikes Back, and put it into a computer division.

Walter Isaacson:

To lead his graphics team, Lucas hired Edwin Catmull, a computer scientist on the cutting edge of the CGI movement, who would later found Pixar. With ILM’s dedicated team of experts and resources, Catmull was soon able to build CGI characters. But other filmmaking technology had to catch up. Optical printers were still being used to combine these new CGI characters with live action backgrounds. And the results were far from seamless.

Dennis Muren:

There were always lots of flaws that would show up, and I’m very sensitive to that. The audience is very sensitive. It used to be you would see little blue lines around characters, or dark areas, or something that just looked off, that you could tell they were shot in different worlds.

Walter Isaacson:

So in the early 1990s, Muren decided to look into new, faster computers, to see if they might be capable of addressing this issue. Eventually, Muren discovered digital compositing software, a new technology that can combine images on a computer instead of on an optical printer. It integrated CGI more seamlessly with background images, creating a more realistic visual experience. Buoyed by his discovery, Muren turned his attention to a new film: Jurassic Park. Already well into production, director Steve Spielberg was set on using dinosaur models in the film. Muren suggested he try CGI instead.

Dennis Muren:

I was unsure that we were ready to do it yet, and I talked to a lot of the CG guys. They said, “We’re not ready yet. We’re not ready yet.” And a couple of the guys were excited, but nothing had been done like that before.

Walter Isaacson:

Muren and his team were given three months to create a CGI dinosaur to show Spielberg. When the three months were up, Muren held a viewing.

Dennis Muren:

I was a little uncertain about what he was going to think, because very few people had seen the test. I made sure the test was the hardest thing it could ever be. It was a Tyrannosaurus just walking along in broad daylight. It’s about eight seconds. It walks by the camera, you get a good view of its face, its legs and everything. You were not trying to hide anything. It’s all got to work there. And so the question was, by the time we got through the end of it, I said I think I believe this. I believe it, will Steven believe it? Because he’s the audience. And he did, and he was just really excited. He said, “This is great. It’s fantastic. We have to change the entire production and everything, and do it this way. And good luck, guys.”

Walter Isaacson:

In the end, they used a masterful blend of CGI and robotics. The result was a groundbreaking film that holds up almost 30 years after its release. Today, it’s widely accepted that contemporary computer-generated imagery owes a debt of gratitude to Dennis Muren and his team. After Jurassic Park, many films started using CGI, but these computer-generated creations rarely interacted with their live action counterparts.

Eric Saindon:

I got a call from a guy in New Zealand that said, “Hey, we’re doing a project here and we want you to come down for six months. We don’t know how it’s going to go. We don’t know how big it’s going to be. Are you willing to move around the world?”

Walter Isaacson:

This is Eric Saindon, the Senior Visual Effects Supervisor at Weta Effects.

Eric Saindon:

I said yes and packed up, and it’s now been 23 years. And I came down for Lord of the Rings, and it turned out it was pretty big.

Walter Isaacson:

Saindon was tasked with helping to create Gollum, a CG character credited with helping change how computer generated effects are used in film.

Eric Saindon:

Back in the day, back on Lord of the Rings, we knew we had this CG character, Gollum. And we knew we wanted to use motion capture, but it was very early days for motion capture. It was pretty rough. The little balls we stuck to Andy, to his suit, they didn’t do a whole lot.

Walter Isaacson:

British actor Andy Serkis was fitted with a motion capture suit. Essentially a leotard fitted with sensors, so his performance, with the aid of CGI software, could be translated into Gollum’s movements. In the first two Lord of the Rings films, Saindon filmed Serkis separately from other actors, on a motion capture stage. It was a complex setup consisting of almost 80 cameras used to capture his movements. He then digitally layered Gollum on top of Serkis’s performance and added him to scenes in post-production. But to get the most realistic blend of CGI and live action, Saindon knew he had to find a way to get Serkis on set, interacting with the other actors. But to film Serkis on a live action set, Saindon had to figure out how to negotiate his 80 motion capture cameras around the hanging lights, blue screens, epic sets, and the film’s other actors.

Eric Saindon:

One of the real tricks for our motion capture team is hiding all these cameras. We are a art director’s nightmare, because our guys basically just go in and start cutting holes in sets, in these beautiful sets they’ve built. And we stick cameras through walls, and then we have to go in in post and actually paint all our cameras out.

Walter Isaacson:

But by the third film in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Return of the King, this hard work paid off.

Eric Saindon:

We actually did a couple scenes where we were able to capture Andy onset in a suit. It was when he was wrestling with Sam, which is the first step into the way we do everything now, where everything is always captured together if we can. And it gives you much better performance, which then in turn gives you the best composition, because the characters are in the right place in space, and interacting at the same time. And he became a character that was no longer just a CG character to throw into a movie just to have a CG character. He became one of the characters of the movie, and you never questioned it.

Walter Isaacson:

In Saindon’s next film, a new take on King Kong, with the title character also played by Andy Serkis, motion capture was pushed forward once again. Needing the audience to go on the giant ape’s emotional journey, motion capture dots were placed on Serkis’s face. And a camera was attached to a headpiece so they could capture his most subtle expressions. The level of human nuance expressed in Serkis’s portrayal of King Kong opened the doors for CGI characters to star in leading roles.

Eric Saindon:

And jumping forward from King Kong, we jumped into Avatar, where we could actually get all our characters moving together, interacting together, and we really jumped into capturing the facial in a much better way and much more detail. That’s when we started really calling it performance capture instead of motion capture, because we felt like we were really getting the entire performance, and getting the emotion of the characters instead of just the base motion.

Walter Isaacson:

Released in 2009, James Cameron’s Avatar was a game changer for the film industry. It used special 3D cameras capable of mimicking the movements of the human eye. That, when paired with its cutting edge facial performance capture technology, created some of the most realistic digitally rendered visuals ever seen on the big screen. But even with this new technology that could capture the subtle expressions on an actor’s face, CGI was still being used to layer fictional characters over the faces of live actors. One famous filmmaker wanted to go a step further, and alter his actors’ actual faces in real time.

Pablo Helman:

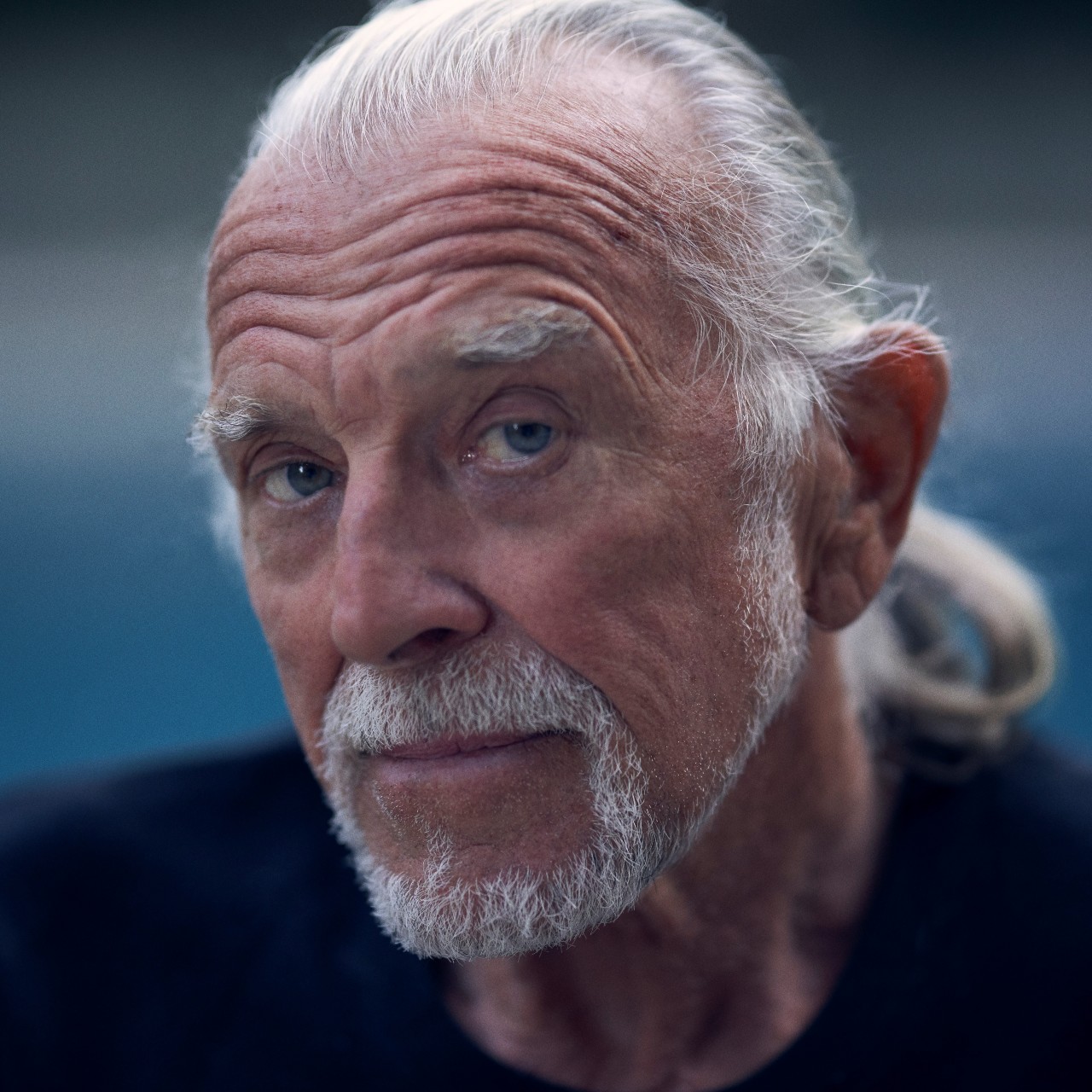

When we started the Irishman, it was a project that had a lot of promise, because it was asking us to do something completely different.

Walter Isaacson:

That’s Pablo Helman, a visual effects supervisor at Industrial Light and Magic. Helman was hired as a Visual Effects Lead on The Irishman, a Martin Scorsese film requiring actors Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Al Pacino to be de-aged by decades. But Scorsese didn’t want his actors to be fitted with motion capture sensors and markers to record their facial expressions.

Pablo Helman:

So Marty Scorsese says, “If we are doing this project, you’re going to have to think about a way to capture their performances without markers.” And so, I got on the phone with ILM and I said, “We need to come up with a technology.”

Walter Isaacson:

He began by building a rig that aimed three cameras at a single actor, which captured a 3D rendering of their performance. He soon realized that he needed the actors to be fully lit, but he wasn’t able to convince the art directors to change the lighting. Then, inspiration struck.

Pablo Helman:

Somebody said, “What if we did it in a way so that nobody can see it?” Well, we have to modify the cameras and we have to throw infrared light onto the actors. But we all learned to work together, and we shot for 110 days or something like that.

Walter Isaacson:

The idea worked. Using a combination of on-set lighting and powerful infrared lights, Helman was able to gather enough surface texture information that a computer could in turn, increase or decrease that texture, changing the actor’s age. And with the three cameras running at the same time, there was enough data to replace the image capture markers used during motion capture.

Pablo Helman:

It was the first project ever, that allowed the actors to capture their performance without markers. And the actors were delighted. And Marty was delighted too, because there in no circumstance did we say to him, “You cannot have that shot.” We figured out a way to do it.

Walter Isaacson:

The result was an all-star cast of Scorsese’s favorite Hollywood gangsters looking decades younger. While filming The Irishman, Helman would occasionally turn to a new technology he thinks could be the future of filmmaking: artificial intelligence. He realized that if he asked an AI program for a specific image of De Niro, say at 40 years old, smiling slightly with the sun hitting his face, the program would scan thousands of online images of De Niro, and create the requested image.

Pablo Helman:

So that’s how we checked our work. It wasn’t good enough in terms of resolution, for us to put those images in the movie because we were rendering all that stuff in CG. But we were checking our work in AI.

Walter Isaacson:

But as the resolution improves, some think that AI might take the visual effects industry in a problematic direction. Deep fakes are AI-generated synthetic videos of people whose face, body or voice has been digitally altered so that they appear to be someone else. And they have led to some uncomfortable questions within the film industry. Could AI one day replace actors? Maybe. But the real question is, even if we can replace actors with AI generated renderings, should we? Because no matter how far visual effects progress, at its core, its purpose is to help filmmakers and actors tell meaningful stories. There’s an inherent human quality in storytelling that can’t be replicated, even by the most groundbreaking visual effects. John Dykstra.

John Dykstra:

When I look at this AI stuff, people get bogged down in all of the clever tricks it can do, but the tricks are never the soul of the performer. The soul comes from a willingness to create an empathy between yourself and the people that you’re performing for. I think the future of visual effects is that it will become more accessible, and that the people who are out there who have unique stories to tell, will be able to use it as an effective tool to create environments or characters that they couldn’t have created with practical solutions. And if anything, that contributes to the success of their storytelling.

Walter Isaacson:

From epic battles in space, and magical creatures from other planets, to removing a wrinkle or tint from an actor’s face, visual effects can be found in films across all genres. And even as the line blurs between what is real and what isn’t, there’s no denying that visual effects bring something to film that audiences will always crave: magic.

It looks like we’ve reached the end of the trail for Trailblazers. This will be the last new episode of the podcast for the foreseeable future. But starting next month, we’re re-airing some of my favorite episodes from our archives to tide you over until we’re back with something new. It’s been an absolute pleasure bringing new stories of trailblazing innovators over the past six years. I hope you’ve enjoyed listening to the show as much as I’ve enjoyed producing it. I’m Walter Isaacson, and you’ve been listening to Trailblazers, an original podcast from Dell Technologies, who believe there’s an innovator in all of us. If you want to find out more about the guests on today’s show, please go to delltechnologies.com/trailblazers. Thanks for listening.

Craig Barron

is a visual effects artist and Creative Director at Magnopus. Barron has contributed to the effects on more than 100 Films including such films as Star Wars: Episode V -The Empire Strikes Back, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Barron is also a film historian, author, and educator with a focus on the history of visual effects produced in classic films, before and after the digital age.

Craig Barron

is a visual effects artist and Creative Director at Magnopus. Barron has contributed to the effects on more than 100 Films including such films as Star Wars: Episode V -The Empire Strikes Back, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Barron is also a film historian, author, and educator with a focus on the history of visual effects produced in classic films, before and after the digital age.

John Dykstra

is a pioneering visual effect artist who has helped transform the film industry with his work on classic films like Star Wars. Since Dykstra co-founded “Industrial Light and Magic” with Star Wars creator George Lucas in 1975, he went on to design visual effects for more than 35 films and has three Academy Awards for his work.

John Dykstra

is a pioneering visual effect artist who has helped transform the film industry with his work on classic films like Star Wars. Since Dykstra co-founded “Industrial Light and Magic” with Star Wars creator George Lucas in 1975, he went on to design visual effects for more than 35 films and has three Academy Awards for his work.

Dennis Muren

is a Consulting Creative Director of Industrial Light & Magic. A recipient of eight Oscars for Best Achievement in Visual Effects and a Technical Achievement Academy Award, Muren is actively involved in the evolution of the company, as well as the design and development of new techniques and equipment.

Dennis Muren

is a Consulting Creative Director of Industrial Light & Magic. A recipient of eight Oscars for Best Achievement in Visual Effects and a Technical Achievement Academy Award, Muren is actively involved in the evolution of the company, as well as the design and development of new techniques and equipment.

Eric Saindon

is a Senior VFX Supervisor at Wētā FX. Saindon joined Wētā FX in 1999 as a Creatures / Character Supervisor, where he was pivotal in the creation of Gollum for The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. He has just wrapped on another James Cameron project as Wētā FX’s Senior VFX Supervisor on Avatar: The Way of Water.

Eric Saindon

is a Senior VFX Supervisor at Wētā FX. Saindon joined Wētā FX in 1999 as a Creatures / Character Supervisor, where he was pivotal in the creation of Gollum for The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. He has just wrapped on another James Cameron project as Wētā FX’s Senior VFX Supervisor on Avatar: The Way of Water.

Pablo Helman

is a visual effects supervisor known for pushing technology to the next level to achieve the vision of filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg. No stranger to innovation, Helman oversaw the development of the creative approach and technology used to achieve the groundbreaking de-aging work created for Martin Scorsese’ The Irishman for which he served as the overall visual effects supervisor.

Pablo Helman

is a visual effects supervisor known for pushing technology to the next level to achieve the vision of filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg. No stranger to innovation, Helman oversaw the development of the creative approach and technology used to achieve the groundbreaking de-aging work created for Martin Scorsese’ The Irishman for which he served as the overall visual effects supervisor.